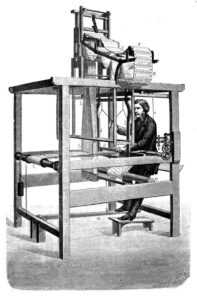

Weaving fibers to form a fabric has been a part of human existence since ancient times. Weaving is the process of interlacing longitudinally oriented warp threads with horizontally oriented weft threads to form a woven fabric. Weaving is performed on a loom, a device arranged to hold warp threads under tension while allowing the weft threads to be sequentially added to them, to produce a fabric. The relative movement and positioning of the warp and weft threads during the weaving process results in a sequence of thread placements that together form a pattern in the finished fabric. To change patterns, the sequence of thread placements must be modified, a traditionally labor and time intensive process. Through the centuries, looms have had a variety of configurations, but their basic function has remained the same.

placements that together form a pattern in the finished fabric. To change patterns, the sequence of thread placements must be modified, a traditionally labor and time intensive process. Through the centuries, looms have had a variety of configurations, but their basic function has remained the same.

Loom technology has seen a variety of innovations throughout history in a continuous effort to make fabric production faster, easier, and more cost-effective. The Jacquard machine invented by French weaver Joseph-Marie Jacquard (born 1752 in Lyon, France) revolutionized the field of weaving. His invention, which uses punch cards to represent a desired sequence of thread placements during operation of the loom, greatly reduced the labor involved in the process of weaving. Jacquard designed a device that would be attached to a loom to control the placement of individual warp threads according to a pre-set progression of steps represented and controlled by a pattern of holes in each of a set of punch cards. This allowed looms to not only produce complex textile patterns such as brocade, damask, and lace, but also to be changed quickly from one pattern to another. By simply exchanging a first set of punch cards for a second set of punch cards, the loom could be reprogrammed to produce a new fabric pattern. Jacquard looms are used for weaving all sorts of intricate patterned textiles. They could be programmed to weave a single pattern fabric or a combination of patterns with different colors. Continue reading “Programming Fashion”

US FDA Seeks Head of Human Foods, Looks to Move Cosmetics Work

Duane Morris attorney Kelly Bonner was quoted in an article in Chemical Watch on March 3.

“The US Food and Drug Administration has started its search for a deputy commissioner for its new human foods programme, and plans to move certain cosmetics functions to another part of the agency to advance oversight of the products. […]

The inclusion of cosmetics in the proposed restructuring is “very significant”, said Kelly Bonner, associate with law firm Duane Morris. Continue reading “US FDA Seeks Head of Human Foods, Looks to Move Cosmetics Work”

Sephora Disputes “Misleading” Allegations in Clean Beauty Class Action Lawsuit

Introduction

On March 2, 2023, Sephora filed its reply in support of its motion to dismiss proposed class action claims that its “Clean at Sephora” program was false and misleading, disputing allegations that a significant portion of relevant, reasonable consumers were or could be misled about what ‘Clean at Sephora’ means, and that the ingredients permitted by Sephora’s program were potentially harmful to humans.

means, and that the ingredients permitted by Sephora’s program were potentially harmful to humans.

Sephora’s reply (presumably) concludes preliminary briefing in what has become a closely-watched lawsuit in the beauty and wellness industry over the meaning of the term “clean beauty.”[1] Absent clear regulatory guidance from the FDA and the FTC, companies’ claims involving the terms “clean,” “natural,” “nontoxic,” or “organic” have been scrutinized in social media, and by an increasingly active and organized plaintiffs’ bar.

While it remains to be seen how the court will decide the “Clean at Sephora” case, companies should continue expect more litigation in this area, as what it means for beauty products to be clean, natural, nontoxic, or safe, remains the subject of intense debate.

Case Background

As explained in our previous publications (here, here, and here), the market for clean beauty is expected to reach an estimated $11.6 billion by 2027.[2] But absent clear regulatory guidance about what it means for beauty products to be “clean,” “natural,” “nontoxic,” or “safe, promoting products as “clean” can carry significant regulatory risks, and leaves the industry ripe for class action litigation.

Sephora launched its “Clean at Sephora” program in 2018.[3] To qualify for inclusion in the program, which spans across various product categories, products must be formulated without certain common cosmetic ingredients—such as parabens, sulfates SLS and SLES, phthalates, formaldehyde and more—that are linked to possible human health concerns.[4]

On November 22, 2023, Plaintiff Lindsay Finster filed a proposed class action lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of New York, alleging that products advertised as part of the “Clean at Sephora” program contain ingredients that are “inconsistent with how consumers understand” the term “clean.”[5]

According to plaintiff, consumers understand the definition of “clean” beauty to mean the dictionary’s definition of “clean”: “free from impurities, or unnecessary and harmful components, and pure.”[6] Thus, to be considered “clean” in the context of beauty, plaintiff alleged that products should be “made without synthetic chemicals and ingredients that could harm the body, skin or environment.”[7] But, as plaintiff contended, “a significant percentage of products with the ‘Clean at Sephora’ [seal] contain ingredients inconsistent with how consumers understand the term.”[8] Consequently, plaintiff alleged that the “Clean at Sephora” program “misleads consumers into believing that the products being sold are “natural,” and “not synthetic” and to paying a price premium based on this understanding.”[9]

Plaintiffs alleged potential class action violations of §§ 349 and 350 of New York’s General Business Law (“NY GBL”), as well as multi-state consumer protection statutes, and breach of express and implied warranty, the Magnuson Moss Warranty Act, fraud, and unjust enrichment claims.[10]

Sephora’s Motion to Dismiss

On February 2, 2023, Sephora moved to dismiss plaintiff’s complaint, arguing that “[i]t is not plausible that reasonable consumers are or could be confused by the ‘Clean at Sephora’ program” for several reasons.[11]

First, Sephora argued that plaintiff relied on unsupported and conclusory allegations about consumers understanding of the word “clean.”[12] While plaintiff argued that consumers understood the definition of “clean” beauty to mean the products made without synthetic chemicals and or potentially harmful ingredients, Sephora countered that plaintiff failed to plead any facts showing that a significant portion of relevant reasonable consumers could be misled by Sephora’s claims into believing that the “Clean at Sephora” program consisted of only natural products and ingredients.[13] As Sephora noted, words like “natural,” “organic,” and the like never appeared on the label or elsewhere.[14] Instead, plaintiff relied upon “on selectively quoted blog posts and webpages from small businesses, which not only lack reliability and authority but are presented without evidence that any significant number of consumers have even read them, let alone agreed with them.”[15]

Second, Sephora argued that plaintiff mischaracterized Sephora’s representations as being about the kinds of ingredients included in the program, rather than excluded.[16] Thus, plaintiff was attempting to turn “Clean at Sephora” into “Natural at Sephora”—claims that Sephora did not make.[17] On the contrary, Sephora’s marketing for the program focused on the exclusion of certain ingredients linked to potential human health outcomes.[18] Because Sephora made no representations about the products or ingredients included, it argued that it could not mislead consumers about the safety of included products or ingredients in the program.[19] Moreover, plaintiff failed to plausibly allege that any of the ingredients included in the program were potentially harmful, relying instead on a series of unattributed and unsubstantiated blog posts.”[20]

Finally, Sephora rejected plaintiff’s contention that it forced consumers to scrutinize product lists in contradiction of the Second Circuit’s 2018 decision in Mantikas v. Kellogg, which prohibits the use of ingredient lists on the side of packaging to clarify otherwise misleading presentations where plaintiff failed to identify any misleading conduct by Sephora.[21]

Sephora also rejected plaintiff’s efforts to seek relief under other unspecified consumer protection statutes, arguing that plaintiff failed to plead how the unspecified consumer protection statutes were similar to the NY GBL,[22] and disputed plaintiff’s breach of warranty, consumer fraud, and unjust enrichment claims as duplicative of plaintiff’s NY GBL claims, or otherwise contingent on the same erroneous premise—that the ‘Clean at Sephora’ label is misleading—and thus, equally deficient.[23]

In opposition to Sephora’s motion to dismiss, plaintiff reiterated that it was sufficiently plausible that reasonable consumers would perceive the “Clean at Sephora” as excluding synthetic ingredients, and that “Clean at Sephora” meant free from potentially harmful ingredients.[24] Plaintiff further contended that resolution of her multi-state claims was not ripe until the class certification stage,[25] and that Sephora’s advertising campaign created an express warranty that “Clean at Sephora” products were formulated without potentially harmful ingredients.[26]

In its reply, Sephora argued that reasonable consumers could not interpret the phrase “Clean at Sephora” as limited to only “natural” ingredients when Sephora “prominently explains, in plain terms, exactly what it means by the phrase: ‘formulated without parabens, sulfates sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) and sodium laureth sulfate (SLES), phthalates, mineral oils, formaldehyde, and more.’”[27] Sephora also refuted plaintiff’s efforts to characterize the program’s inclusion of the phrase “and more” into an impression that synthetic ingredients were excluded along with the listed ingredients, noting that plaintiff alleged no facts to support her contention that reasonable consumers shared that impression. [28]

Finally, Sephora rejected what it described as plaintiff’s efforts to conflate the meaning of the word “clean” with “non-synthetic” or “natural,” or otherwise assert that because products are not “natural,” they were not safe, noting that not all synthetic ingredients were unsafe, while not all natural ingredients were safe. [29]

Takeaways

Although the recent Modernization of Cosmetics Regulation Act (MoCRA), which was passed by Congress on December 23, 2022, significantly expands FDA’s authority over cosmetics, it provides comparatively little guidance on the kinds of marketing or promotional claims brands can make about the safety or purity of their products. Consequently, these issues are expected to remain the subject of intense scrutiny and costly litigation.

It remains to be seen how the court will rule in the “Clean at Sephora” case. Nevertheless, this case remains closely-watched within the beauty and wellness industry, and we will continue to update you as the case develops.

[1] See Sephora’s Reply in Support of Motion to Dismiss (“Reply”) at 1, Finster, et al, v. Sephora USA, Inc., No. 6:22-cv-1187 (GLS/ML) (N.D.N.Y.), Mar. 3, 2023 (Dkt. No. 18).

[2] “Cosmetics Companies Invite Legal Risks With ‘Clean’ Marketing,” Law360, September 1, 2022

[3] https://www.gcimagazine.com/brands-products/news/news/21853297/sephora-launches-clean-at-sephora

[4] Sephora Clean Beauty Guide, https://www.sephora.com/beauty/clean-beauty-products

[5] Complaint (“Compl.”) at ¶ 15, Finster, et al, v. Sephora USA, Inc., No. 6:22-cv-1187 (GLS/ML) (N.D.N.Y.), Nov. 11, 2022 (Dkt. No. 1).

[6] Id. at ¶ 2.

[7] Id. at ¶ 2-4.

[8] Id. at ¶ 15.

[9] Id. at ¶ 35.

[10] Id. at 6-10.

[11] Motion to Dismiss at 1, Finster, et al, v. Sephora USA, Inc., No. 6:22-cv-1187 (GLS/ML) (N.D.N.Y.), Feb. 2, 2022 (Dkt. No. 6-1).

[12] Id. at 7-8.

[13] Id.

[14] Id.

[15] Id. at 9.

[16] Id. at 1.

[17] Id. at 7-8.

[18] Id.

[19] Id. at 10-11.

[20] Id. at 11-12.

[21] See 910 F.3d 633, 636–37 (2d Cir. 2018).

[22] Id. at 14.

[23] Id. at 15-19. Sephora also advanced several pleading deficiency arguments, including plaintiff’s failure to allege the product was advertised as “free from defects” as required by the Magnuson Moss Warranty Act.

[24] See Opposition to Sephora’s Motion to Dismiss (“Opp.”) at 4 (Feb. 23, 2023) (Dkt. No. 15).

[25] Id. at 7.

[26] Id. at 8.

[27] See Reply at 3.

[28] Id.

[29] Id. at 4.

Why Beauty Lawsuits Are Set to Increase

Duane Morris attorney Kelly Bonner was quoted in an article in WWD on March 3.

“Beauty companies seem to be coming under increasing fire with lawsuits, fueled in part by the rise of TikTok and other social media platforms, and legal experts are expecting the number of cases to surge. […] Continue reading “Why Beauty Lawsuits Are Set to Increase”

From Home-Made to Store-Bought Fashion

Fashion is a way of creating new and distinctive designs that can be worn by different people in different settings. It is often a reflection of the times in which it is created, but it can also be influenced by, technology, culture, even religion. Before the mid-19th century, most clothing was home-made. Occasionally, a village dressmaker was available to make a made-to-measure dress. The wealthy often employed seamstresses who dealt directly, and often exclusively, with their patron. The rapid mechanization of fabric production led to the appearance of ready-to-wear stores that provided the middle classes an opportunity to move away from home-made garments.

Aniline dye printed fabrics were used for many of the garments that were produced in this period. They were woven according to a manufacturing method that caused the dyes to run down the surface of the fabric. This made the garments more textured and interesting. The process created fabrics that contrasted with the smoother, lighter-colored cottons and linens that were also popular at the time. Aniline dyes could also be applied to other materials to give them a more sophisticated appearance. One example is aniline colored velvet which was very popular through the 1890’s. It was made in a range of colors, from soft pink to dark red and sometimes bright purple. The Aniline colored velvet was a soft, comfortable fabric that clung to the body, revealing the wearer’s shape, and giving it an attractive drape. It was especially popular for evening dresses. Velvet was made in a range of textures, from fine to coarse. It was usually trimmed with delicate embroidery, lace, ribbons and beading. Continue reading “From Home-Made to Store-Bought Fashion”

MoCRA Is Here — Now What? Unpacking Litigation and Regulatory Risk for Cosmetics Brands Following MoCRA’s Enactment

On December 23, 2022, Congress enacted the first major statutory change to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s ability to regulate cosmetics since the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA). Passed with bipartisan and industry support, the Modernization of Cosmetics Regulation Act (MoCRA) significantly expands FDA’s rulemaking and enforcement authority over cosmetics and creates substantial new compliance obligations for manufacturers, packers, and distributors of cosmetics intended for sale in the United States.

Although MoCRA establishes several new requirements concerning product safety, it provides comparatively little guidance on the kinds of marketing or promotional claims brands can now make about the safety of their products.

To read the full text of this article by Duane Morris attorneys Rick Ball, Alyson Walker Lotman and Kelly Bonner, please visit the Duane Morris website.

Color My World: Aniline Dyes in Fashion

The past centuries have seen a variety of cultural and technological shifts, and the fashion world has followed suit. These changes have also had a profound impact on the way we dress. In the 19th century, the commercialization of newly discovered aniline dyes for printed fabrics had a profound impact on fashion. The use of these synthetic dyes changed the way we colored fabrics, allowing manufacturers to scale up production. Aniline dyes made it easy for manufacturers to print on a wide range of fabric types all with consistent hue and tone of the color between batches. This allowed for the reemergence of the dyeing industry, which was formerly languishing because of its long dependency on expensive naturally derived pigments. Continue reading “Color My World: Aniline Dyes in Fashion”

From Coal Tar to Couture: The Discovery of Aniline Dyes and The Effect Upon Fashion

Around 1856 an 18-year-old British chemist named William Henry Perkin changed the world of fashion forever. He had been performing experiments seeking to replace the natural anti-malarial drug quinine. Instead of the colorless powder he had expected, he found that oxidizing aniline, a coal tar derivative, produced a reddish powder containing something far more exciting: an intense purple. Fashion would never be the same! This discovery led to the wide commercial availability of low cost, brightly colored fabrics that would be available to all. It also marked the beginning of a hugely profitable business. Continue reading “From Coal Tar to Couture: The Discovery of Aniline Dyes and The Effect Upon Fashion”

Duane Morris Attorney Kelly Bonner Talks Cosmetics Regulations and More on This Week’s Episode of “Fat Mascara” Beauty Podcast

Join Duane Morris attorney Kelly Bonner as she discusses America’s complex system of cosmetics regulation on the award-winning beauty podcast, Fat Mascara, hosted by Jennifer Sullivan (beauty columnist, The Cut) and Jessica Matlin (beauty director, Moda Operandi).

Links to Episode 474: How Cosmetics Are Regulated, with Kelly Bonner, below

Taking a Bite Out of the Brand?

By Brian Siff and Victoria Danta

Is imitation the sincerest form of flattery? Not according to brand owner Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc., (“JDPI”), which owns the JACK DANIEL’S source identifiers for alcoholic beverages and other goods – most notably, whiskey.

For the better part of a decade, JDPI has been embroiled in a dispute with toy maker VIP Products LLC, (“VIP”), which makes humorous chew toys that allegedly parody well-known products. The toy shown below is at the center of this dispute, and features elements of authentic Jack Daniel’s® whiskey bottles and labeling, and dog-related puns, such as “BAD SPANIEL,” “OLD No. 2,” and “TENNESSEE CARPET”:

|

VIP Chew Toy |

JDPI Bottle and Labeling |

|

|

In 2014, JDPI accused VIP of trademark infringement and demanded that VIP cease all sales of the BAD SPANIELS chew toy. VIP then sued for a declaratory judgment, including a declaration of non-infringement. JDPI counterclaimed for infringement and related causes of action, including dilution of a famous trademark. The U.S. District Court for the District of Arizona applied a traditional “likelihood of confusion” analysis to JDPI’s claims, finding that confusion was likely on the basis of evidence that included actual confusion and a consumer survey. Notably, JDPI’s brand licensing program included pet products.

The District Court allegedly erred by not appropriately considering the First Amendment’s free speech protections and specifically, it did not properly consider the idea that the chew toy was a humorous parody, and that it was an expressive work entitled to protection.

In early-2020, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled that the toy was, indeed, an expressive work protected by the First Amendment. Thus, VIP’s use of JDPI’s source identifiers was not actionable infringement, dilution or tarnishment. The Ninth Circuit held that the traditional likelihood of confusion test failed to account for the public interest when free speech rights are involved. The Ninth Circuit emphasized the toy’s humorous messages. Ultimately, the Ninth Circuit sent the dispute back to the District Court for further proceedings on JDPI’s infringement claims. Critics point out that the Ninth Circuit was the first anywhere to apply such strong free-speech protections, and that the holding conflicts with decisions from other Courts of Appeals (including the Second Circuit). Furthermore, some argue, the Ninth Circuit’s decision could encourage trademark infringement, by appearing to offer infringers protection if they can allege some minimal “humorous” aspect to their product.

When the dispute then returned to the District Court, the Court ruled for VIP, finding that the chew toy did not infringe upon JDPI’s rights, and that it was creative expression was protected by the First Amendment. However, the District Court encouraged the parties to appeal to the SCOTUS, as it believed the Ninth Circuit’s decision would create significant uncertainty.

Initially, SCOTUS rejected JDPI’s Petition for Certiorari, but JDPI was persistent; with the further urging of the District Court, JDPI repetitioned SCOTUS, and SCOTUS agreed to hear the appeal in late-November 2022.

The issues SCOTUS will resolve are as follows:

1) “Whether humorous use of another’s trademark as one’s own on a commercial product is subject to the Lanham Act’s traditional likelihood-of-confusion analysis, or instead receives heightened First Amendment protection from trademark-infringement claims.”; and

(2) “Whether humorous use of another’s mark as one’s own on a commercial product is ‘noncommercial’ under 15 U.S.C. §1125(c)(3)(C), thus barring as a matter of law a claim of dilution by tarnishment under the Trademark Dilution Revision Act.”

Various third parties have filed amicus briefs on the issue, including the American Intellectual Property Law Association, (AIPLA); Campbell Soup Company; Levi Strauss & Co. and Patagonia Inc.; and the International Trademark Association, (INTA).