- A helical wind turbine design by Change Wind Corporation was denied registration as a trademark because the design was deemed functional rather than ornamental, and Change Wind was unable to prove that customers knew the source of the design.

- It can be difficult to register product designs as trademarks once the features of the design are the subject of a patent application.

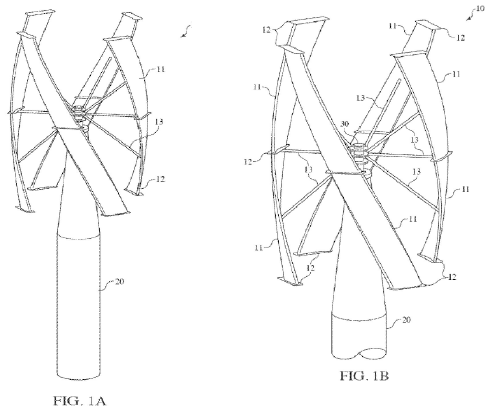

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office denied an application by wind turbine manufacturer Change Wind Corporation to register its helical turbine design (shown below) as a trademark. The denial likely ends Change Wind’s quest to be granted exclusive rights to the registration of this specific design.

Change Wind’s Helical Turbine Design

A trademark is something that identifies the source of a product or services. A trademark can be a word, symbol, sound, logo, or even a color. For example, NBC Universal has trademarks on “NBC,” the NBC peacock logo, and the NBC chimes that play at the beginning of broadcasts. Each of these things identifies the broadcast as originating from NBC.

Companies that use trademarks are entitled to the exclusive use of those marks, and – unlike with patents – those rights may be maintained in perpetuity. Since the trademark identifies the source of a product or services, a grant of exclusive use to the owner of the trademark prevents confusion among customers. If I see a pair of shoes at the store with a Nike swoosh on the side, I know that the swoosh represents the source of those shoes, and I have some expectation (good or bad) as to the quality of the shoes. Trademarks are, in some form, simply an efficient method for consumers to identify and differentiate between sources of products. Some like to think of trademarks as a “badge of origin.”

The design of a product or its packaging may also constitute a trademark. (This type of trademark is called “trade dress” because it refers to how the product is “dressed” for marketing.) However, it is important to note that trademark protection does not extend to product designs that are functional. Protection for functional designs is provided under patent law. Trademarks can only be used to protect ornamental designs.

Which brings us back to Change Wind. In order to register their helical turbine design, [See Note 1 below] Change Wind needed to affirmatively answer two key questions:

(A) Is the turbine’s design driven by ornamental – as opposed to functional – considerations?

(B) Do consumers see the helical turbine design and know that Change Wind is the source of that turbine?

In evaluating the Question A, the USPTO evaluates four factors:

(1) the existence of a patent disclosing the utilitarian advantages of the design;

(2) advertising materials that tout the design’s utilitarian advantages;

(3) the availability of functionally equivalent designs; and

(4) whether the design results in a comparatively cheap or simple method of manufacture.

For the first factor, Change Wind is the owner of U.S. Patent No. 9,103,321. The company’s CEO is named as the inventor of the patent, and the patent largely describes the structure and advantages of the features of the helical wind turbine shown in Figures 1A and 1B:

From the patent’s description of the utilitarian advantages of the design, the USPTO concluded that the first factor weighs in favor of finding the helical design to be functional rather than ornamental.

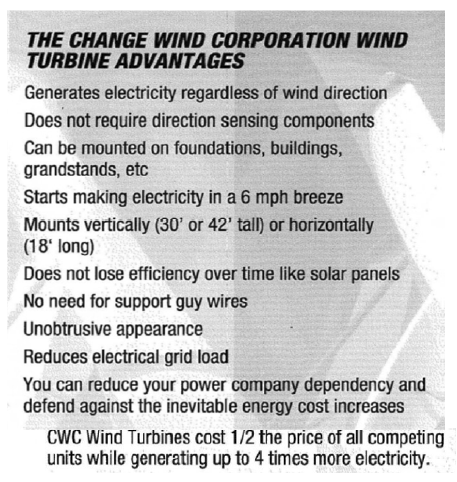

In evaluating the second factor – advertisements – the USPTO looked at some of Change Wind’s product brochures. These documents appear to list functional advantages of certain features of the Change Wind design and thus provide further evidence that the design is functional instead of ornamental. For example, the brochure shown below lists several advantages of Change Wind’s helical design such as generating electricity “regardless of wind direction,” and “no need for support guy wires.”

For the third factor the USPTO considered about 30 helical turbine designs that Change Wind had submitted as “alternative designs.” However, the USPTO determined that many of the designs were merely variations on the Change Wind design and therefore not truly alternatives. The USPTO thus found the third factor to weigh in favor of a finding that the design is functional.

The USPTO evaluated the fourth factor as unknown and therefore neutral in the functionality analysis. In weighing the four factors, the USPTO found that the evidence in this case showed the helical design to be functional and therefore ineligible for registration as a trademark.

The USPTO also answered Question B in a manner unfavorable to Change Wind. As the applicant, Change Wind needed to show that relevant consumers recognized the Change Wind turbine and knew that it came from a single source. Evidence that the USPTO usually considers when answering Question B includes surveys of relevant consumers, sales data, advertising expenditures, the use of the trademark in advertising, length and exclusivity of trademark use, media recognition or awards given for the trademark, evidence of others copying the trademark, and evidence of consumers being confused when others copied the trademark.

Change Wind’s evidence on this point appeared to underwhelm the USPTO. Change Wind could show only $3,000 in marketing expenditures, limited media coverage, and turbine sales of $12M. Without any additional evidence – such as a consumer study showing the helical design to be well-recognized as emanating from a single source – the company could not demonstrate that consumers would view the Change Wind turbine design as a source identifier.

The USPTO decision denying registration of the turbine design could be appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals of the Federal Circuit. It does not appear Change Wind has appealed the decision, which makes the rejection final.

Trademarks can be powerful tools. Trademarks keep competitors from cashing in on the hard work it takes to build a brand. Unlike patents, with appropriate care trademark rights may be maintained indefinitely. Despite the power of trademarks, as the Change Wind case shows, companies must treat trademarks as one piece of the broader IP portfolio. Careful IP professionals view the portfolio holistically in order to de-conflict the various pieces. Here, Change Wind’s earlier efforts to secure a patent for their turbine design later cost them a chance at registering that design as a trademark.

Note 1: Although rights to a trademark arise from the use of the trademark in commerce, most countries also provide an optional system of trademark registration that provides additional benefits to trademark owners. In the United States it is common practice to register a trademark at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

This post was co-authored by Justus Getty and Nicole Candelori.