Duane Morris Takeaway: This week’s episode of the Class Action Weekly Wire features Duane Morris partners Jerry Maatman and Jennifer Riley, as well as associate Greg Tsonis, with their discussion and analysis of FLSA / wage & hour class and collective action litigation trends and rulings from 2022 and predictions for what 2023 may bring for Corporate America. We hope you enjoy the episode.

Episode Transcript

Jerry Maatman: Welcome to our weekly class action review podcast entitled the Weekly Wire. I’m joined by my colleagues Jennifer Riley and Greg Tsonis today to talk about one of our most favorite topics and that is wage and hour class action and collective action litigation. I think as all companies know, this is an area of intense focus by the plaintiffs’ bar and one of the most frequently filed actions throughout the United States. In the last 15 years, the number of FLSA class and collective actions have dwarfed all other types of employment-related litigation. When it comes to certification, Jen, is there a difference between certification of a collective action as opposed to certification of a class action – what does that all mean?

Jennifer Riley: Thanks Jerry, that’s a great question. So as we’ve previously talked about on the podcast, in order to certify class under Rule 23, a plaintiff has to meet the requirements set forth in Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23, such as commonality, typicality, or adequacy. By contrast under the FLSA – of the Fair Labor Standards Act – that statute has its own built-in procedure which courts have called collective action certification. Most courts have applied a two-step process to those FLSA collective actions: at the first stage a plaintiff need only make a modest factual showing that the plaintiff has similarly situated to the individuals that he or she seeks to represent. Then the court will permit the plaintiff to provide notice of the case to that group of folks and allow those folks to opt in and consent to be party plaintiffs to the action. Then at the second stage, the court will actually consider the evidence in terms of whether those individuals are in fact similarly situated. So that second stage occurs you usually after some discovery, and based on a fuller record, and then the court would be considering whether or not the case should proceed to trial on a collective basis.

Jerry: Thank you, Jen – I’ve heard it said that certification or obtaining or blocking it is much like real estate or purchasing real estate: location is everything. Greg, when it comes to standards for collective action certification are federal courts throughout the United States uniform and consistent in their approach?

Greg Tsonis: Great question, Jerry. The Fifth Circuit abandoned that two-stage certification process for FLSA cases in a 2021 case titled Swales, et al. v. KLLM Transport Services, and actually just recently – a few weeks ago the Sixth Circuit changed the standard and that now a plaintiff must first demonstrate a “strong likelihood” that individuals are similarly situated to the plaintiff in order for a district court to authorize notice in an FLSA case.

Jerry: Given the relatively lower bar with those caveats to conditional certification of a Fair Labor Standard Act case, Jen, are the plaintiffs’ attorneys readily successful in converting filed lawsuits into certified lawsuits in this space?

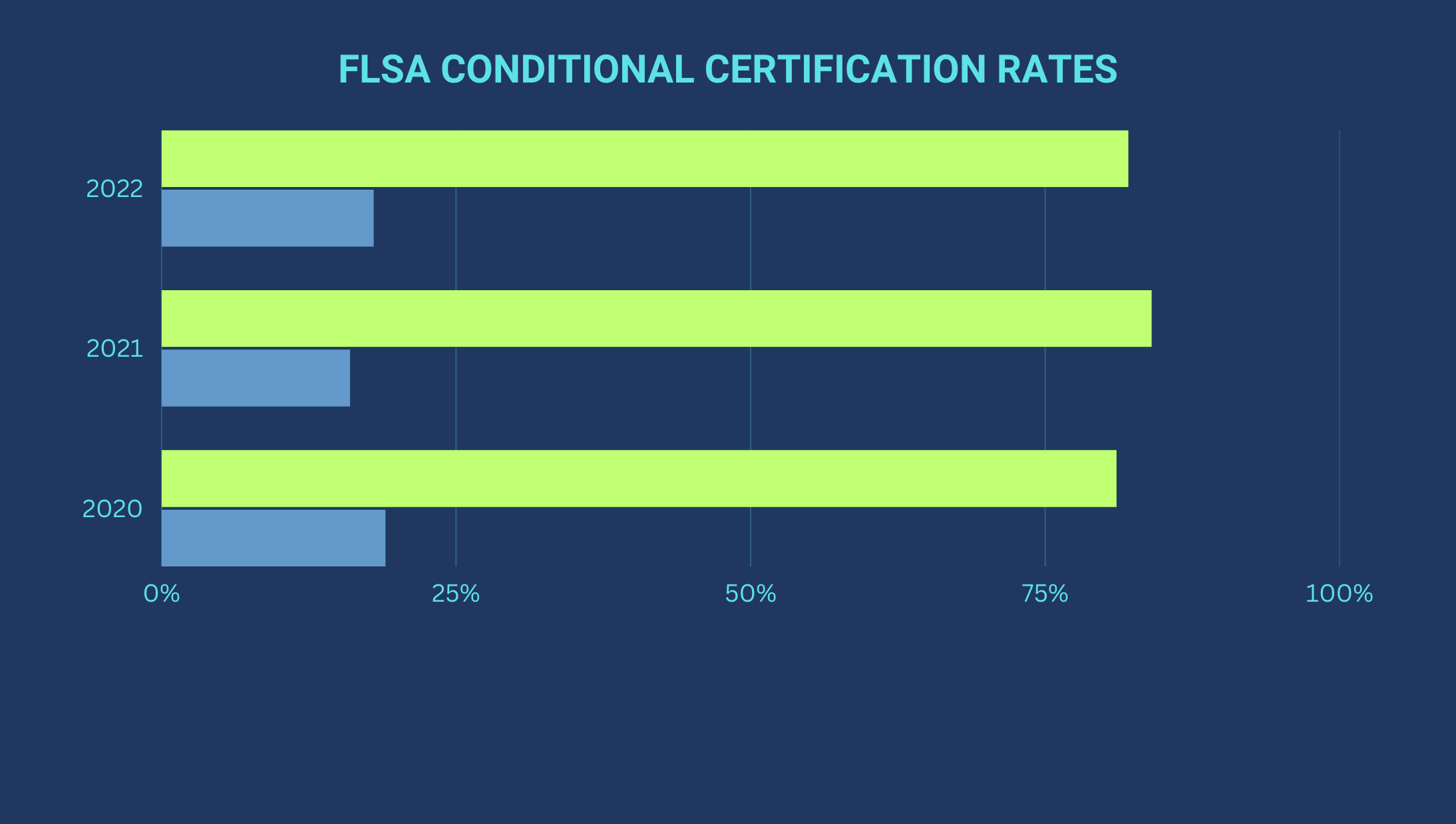

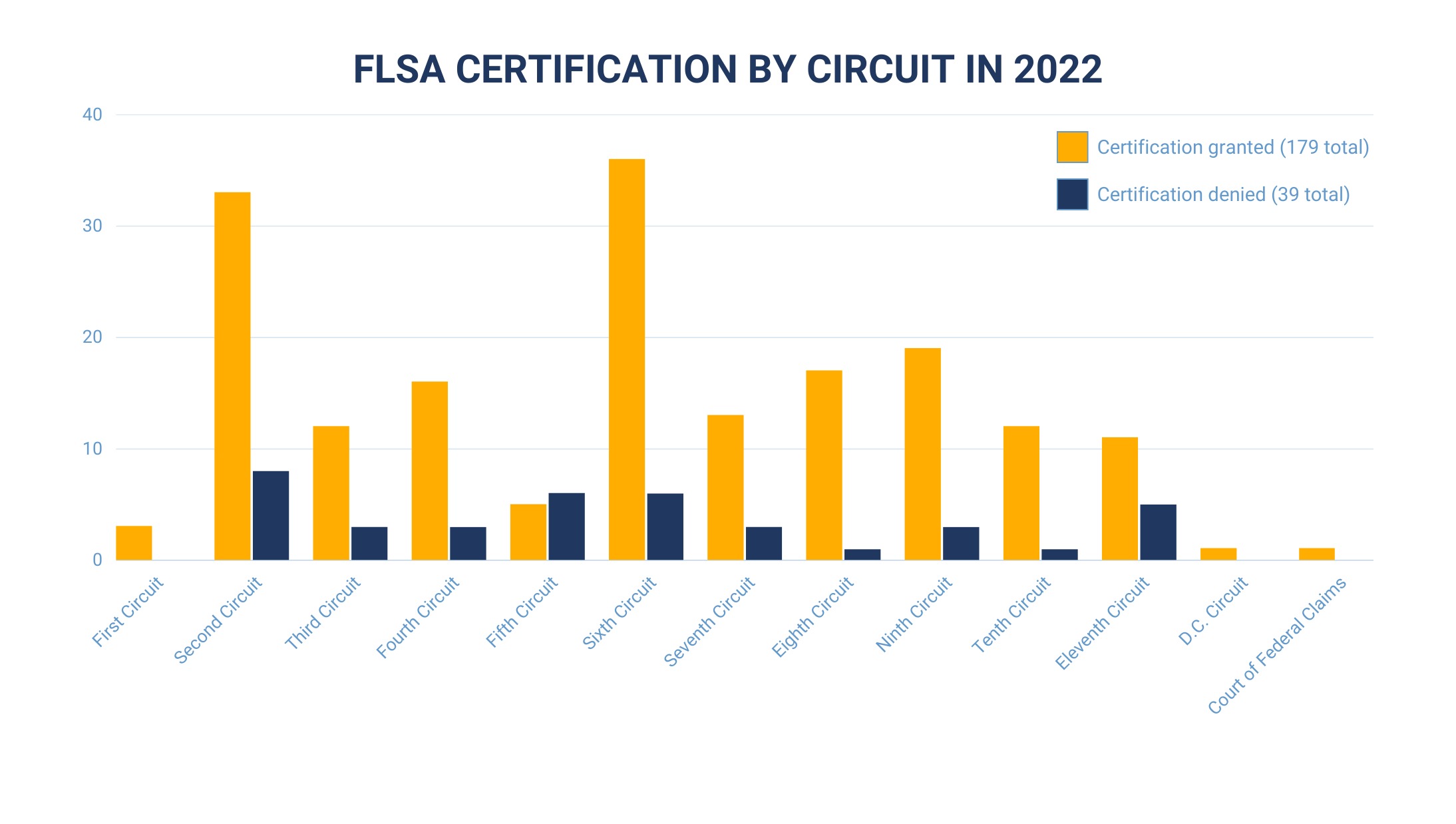

Jennifer: Historically, we have seen the plaintiffs achieve a very high rate of success, particularly on these first stage motions for conditional certification. That trend continued in 2022 – out of 219 rulings the plaintiffs won – in whole or partial part – 180 of those decisions, or 82%, whereas the defendants defeated only 39 motions for the that first stage certification. That’s similar to what we saw in 2021, where the plaintiffs’ bar had a success rate of around 84%, and what we saw in in 2020 where the success rate was around 81% on those first stage motions.

Greg: In the second stage – often brought by defendants in a motion to decertify – defendants had mixed success, a percentage in 2022 of around 50% of those decertification motions granted and 50% of those motions denied. That compares pretty evenly to the numbers in 2021, where about 53% of decertification motions were granted and 47% of those motions were denied.

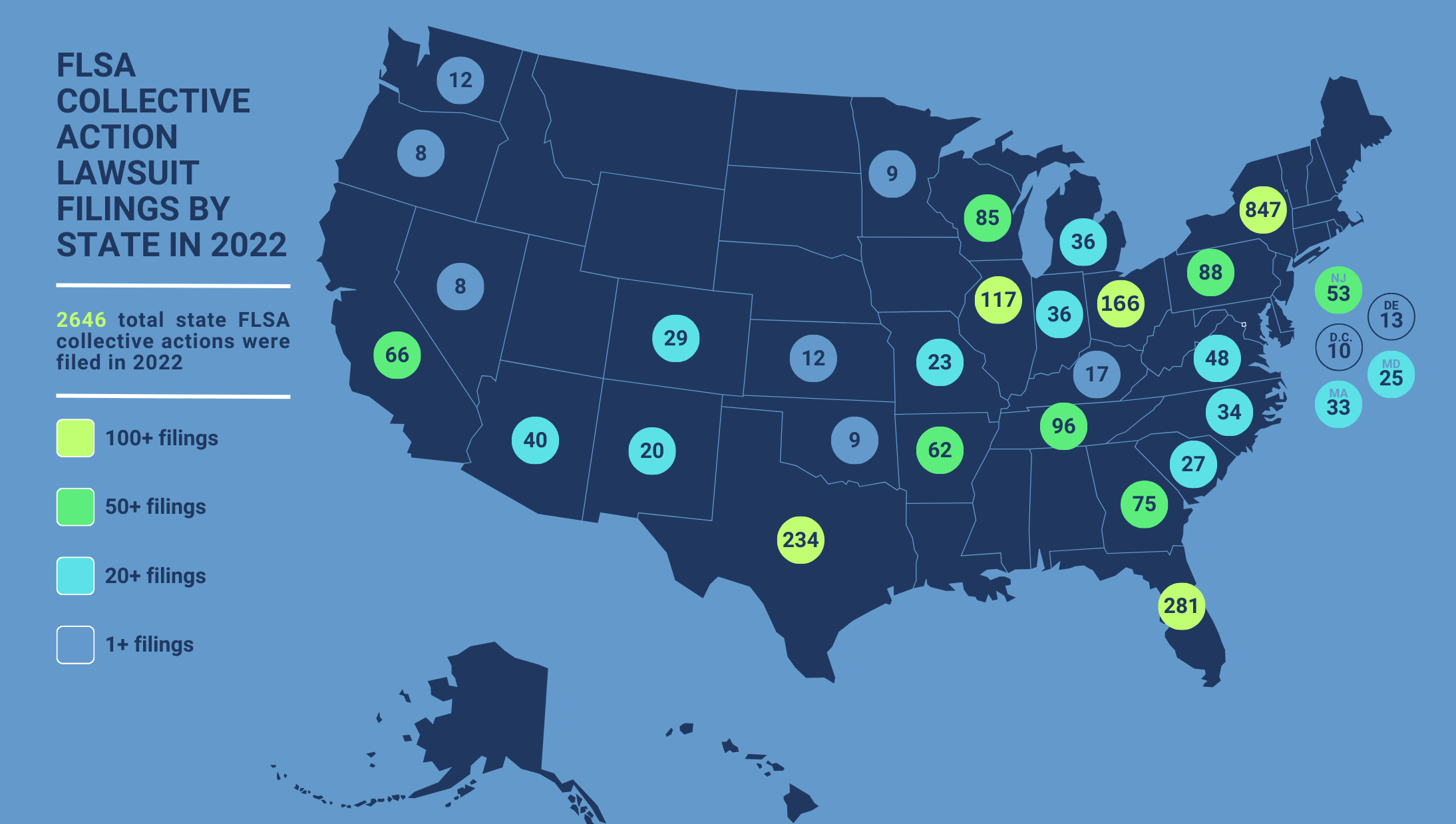

Jerry: Those statistics are very interesting if not compelling. In your experience are there epicenters or magnets for class actions or collective actions in the Fair Labor Standards Act space where the plaintiffs’ bar will more often than not file these larger cases against employers?

Greg: That’s a great question, Jerry. Historically we’ve seen the most FLSA cases filed in the Second Circuit, the Ninth Circuit, and the Sixth Circuit. However now that the Sixth Circuit recently toughened the required showing to issue notice in FLSA cases, we may very well see a decline in FLSA cases filed there.

Jerry: Chapter 13 of the Duane Morris Class Action Review was one of the denser chapters in terms of the number of rulings because as Jen and Greg, you had suggested there are many, many certification rulings. Difficult question, but are there particular rulings over the past year that stand out for particular principles that you would like to share with our viewers?

Jennifer: Thanks, Jerry. One notable ruling came out of the Second Circuit in a case called Campo, et al. v. Granite Services International. In that case the plaintiff was an environmental health and safety advisor, he alleged that his employer had paid him straight time for all of his hours worked, rather than time and a half for hours worked over 40 in a work week. He moved for conditional certification of a nationwide collective action, and he supported that motion with only four declarations. Nevertheless the court accepted the motion and ultimately granted conditional certification of that nationwide collective action, which included all employees across the country who had been paid in a similar way – meaning who had been paid the same hourly rate for all hours worked.

Greg: Plaintiffs that were able to demonstrate the existence of a common policy were also usually able to achieve conditional certification. One key case that demonstrates that is Staley, et al. v. UMAR Services. In that case the plaintiff was a caregiver that alleged a failure to pay overtime compensation for time that was spent working during time that was deemed to be sleeping hours. So specifically the plaintiffs contended that the defendant required the plaintiff and other similarly situated employees to be on call at the defendant’s group homes at night while clocked out, which led to them not receiving allegedly overtime compensation they were owed on occasions where they had to work during that time. To support their case the plaintiffs submitted nine declarations and the court ultimately found that the declaration showed that the defendant did have the allegedly unlawful common policy regarding sleep time for caregivers at its group homes and that the policy affected all the employees at issue, granting conditional certification.

Jerry: Besides off the clock or unpaid overtime claims, Jen, I know that a significant area of focus of the plaintiffs’ bar is what are known as ‘misclassification cases’ where an otherwise exempt employee there’s a debate as to whether or not they should be paid and should not be paid overtime. Were there any particular rulings over the last year in that space that you deemed to be noteworthy?

Jennifer: Thanks Jerry, I absolutely agree misclassification is a very popular theory of the plaintiff’s bar. We’ve seen a lot of cases alleging misclassification as exempt versus non-exempt or hourly as well as misclassification as independent contractor versus employee. One notable ruling in that space is Zambrano, et al. v. Strategic Delivery Solutions. In that case plaintiffs were a group of delivery drivers of pharmaceutical products – they alleged they had been improperly classified as independent contractors they were actually paid on a per-stop basis and they claim that they should have been paid for overtime a time and a half of their regular hourly rate. They also claimed that their employer made improper deductions and forced them to pay for certain expenses that ultimately drove their hourly rate below the minimum wage. In support of their motion for conditional certification, the plaintiffs offered again only four declarations and those declarations were really focused on their alleged common job duties, their common responsibilities, they were based on conversations with numerous other unnamed or unidentified drivers. The defense argued that the evidence wasn’t sufficient – that the plaintiffs in fact worked by themselves, for themselves – and the court ultimately sided with the plaintiffs, rejecting the defense arguments and found that the plaintiffs had sufficiently set forth enough evidence to meet their burden at the conditional certification phase.

Jerry: Let’s pivot to employer-related victories. The statistics that you both shared with respect to certification rates indicating that 82% of the time federal courts were granting plaintiffs’ motions for conditional certification means there’s a box of 18% where employers were successful. A question for both of you, were there particular rulings that would illustrate good strategies for employers to follow to try and get in that 18% space?

Greg: Thanks Jerry, as you mentioned the plaintiffs’ bar has had a substantial success rate in achieving conditional certification but some defendants were able to successfully defeat those motions for conditional certification in 2022 by focusing on the shortcomings of plaintiffs’ proper evidence, particularly focusing on the limited personal knowledge that those declarants had to establish the applicability of you know allegedly common policies to the members of the proposed collective action.

Jennifer: Another ruling that comes to mind is Quinn, et al. v. Vail Resorts, where the plaintiffs were a group of seasonal workers at one of the defendant’s resorts and alleged that the defendant had failed to pay hourly workers for travel time, time spent donning and doffing uniforms and equipment, and training time. The plaintiffs in that case sought to represent over 36,000 hourly employees across various properties. In support of that motion the plaintiffs only supplied three declarations to the court. The magistrate judge in that case found that the plaintiffs had actually failed to meet their burden – they failed to show that the potential collective action members were subject to a single decision, policy, or plan and the magistrate judge instead credited the defendant’s argument that the method and the time spent traveling to parking lots, donning or doffing particular equipment, varied substantially across the various work sites at which these potential collective action members worked.

Greg: Another example is Sutter Valley Hospitals, et al. v. Ward, where that case demonstrated the absence of a central policy can defeat conditional certification. In that case the plaintiffs were surgical technicians who alleged a failure to pay overtime and minimum wage against the employer. The court, in assessing the motion for conditional certification, determined that the plaintiffs’ declarations were just too vague and conclusory to imply that an unlawful practice occurred because they were identical and contained much of the same language with only minor differences based on which facility the declarants worked at and details of their dates of employment.

Jerry: If we pivot to decertification motions, these statistics that you both shared showed it was basically a jump ball – fifty percent of the time or so employers won versus plaintiffs. Are there any shining star examples of great defense rulings, Jen, that came down the last year in the decertification context?

Jennifer: Great question, Jerry. There’s one very notable decision issued in a case called Weeks, et al. v. Matrix Absence Management. In that case the defendant invoked the FLSA’s administrative exemption as a defense to the plaintiff’s claims. That exemption requires the defendant to demonstrate that the individuals exercised discretion and independent judgment with respect to matters of significance, and this case shows that a defendant invoking that defense can use it as a tool to defeat, or to show that decertification is appropriate. So in that case, the main issue was whether the plaintiffs were in fact subject to that exemption. The plaintiffs argued that their judgment, or their discretion and independent judgment, was constrained by things like the customer plan criteria, the defendant’s policies, the supervisors’ audits – but the defense asserted that those constraints themselves varied significantly and that that variation supported decertification. The court agreed with the defendant in that case, and found that the plaintiffs had failed to demonstrate material, factual, and legal similarities within the membership of the group that was part of the collective action, and therefore in that case the court granted the defendant’s motion for decertification.

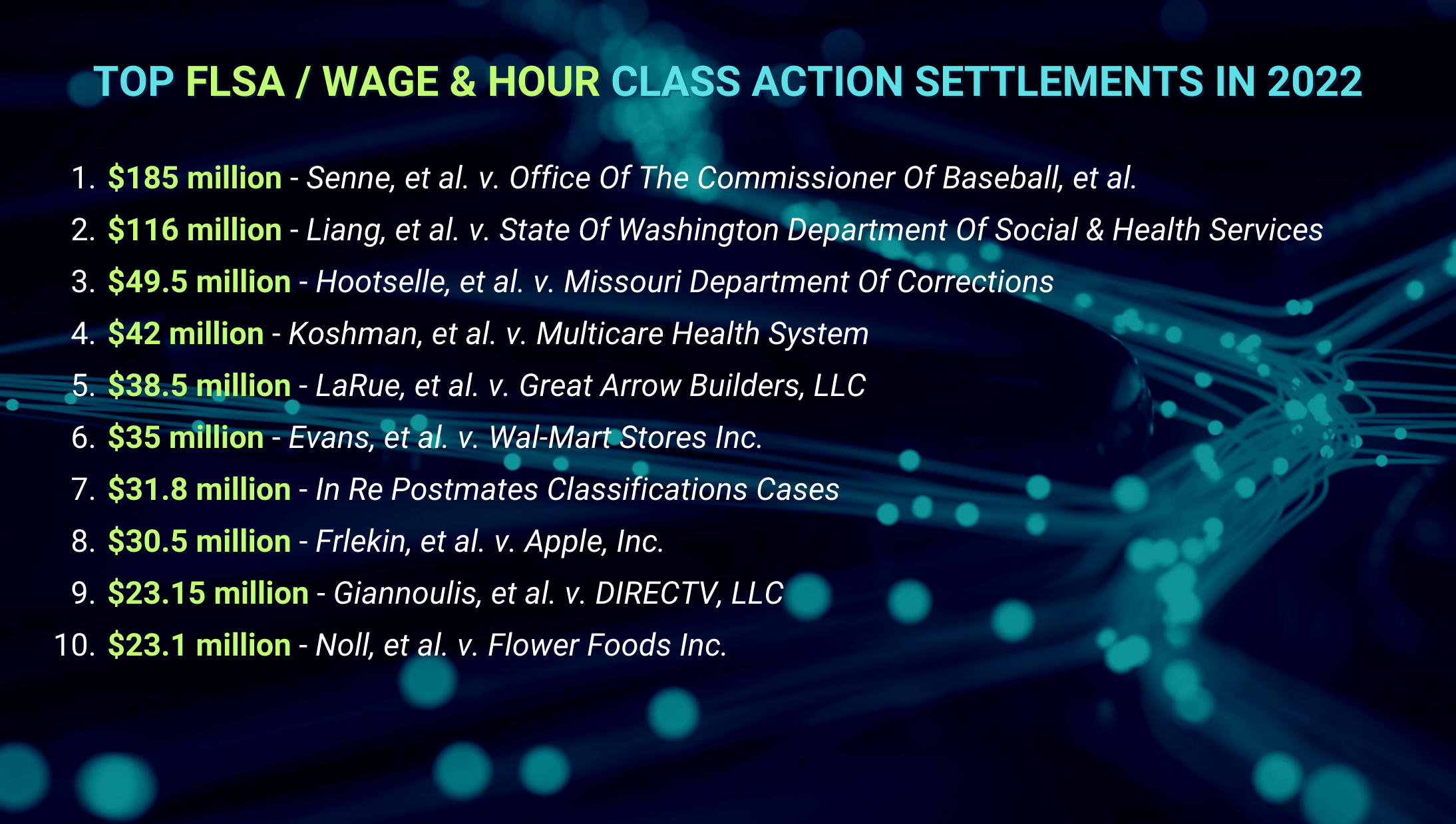

Jerry: Given the certification numbers how has that impacted settlement? Greg, in terms of our study the top 10 settlements in the wage and hour space, were there any particular jurisdictions that stood out in terms of being a magnet for those settlement of those cases?

Greg: There was, Jerry. In 2022, six of the top 10 settlements occurred in California courts, and collectively those settlements totaled just shy of $575 million dollars.

Jerry: Well, Jen and Greg – thank you for your tour of the wage and hour class and collective action world, it’s quite a story that was told last year, and I’m sure 2023 has more in store for employers on this front, so we hope you’ve enjoyed our discussion on our podcast today and thank you so much for tuning in to the Class Action Weekly Wire.