By Gerald L. Maatman, Jr., Jennifer A. Riley, Alex W. Karasik, and Gregory Tsonis

Duane Morris Takeaways: The EEOC’s fiscal year (“FY 2025”) spans from October 1, 2024 to September 30, 2025. Through the midway point, EEOC has filed 23 enforcement lawsuits, an uptick when compared to the 14 lawsuits filed in FY 2024, but still down from the 29 filed in the first six months of FY 2023. Traditionally, the second half of the EEOC’s fiscal year – and particularly in the final months of August and September – are when the majority of filings occur. However, an early analysis of the types of lawsuits filed, and the locations where they are filed, is informative for employers in terms of what to expect during the fiscal year-end lawsuit filing rush in September.

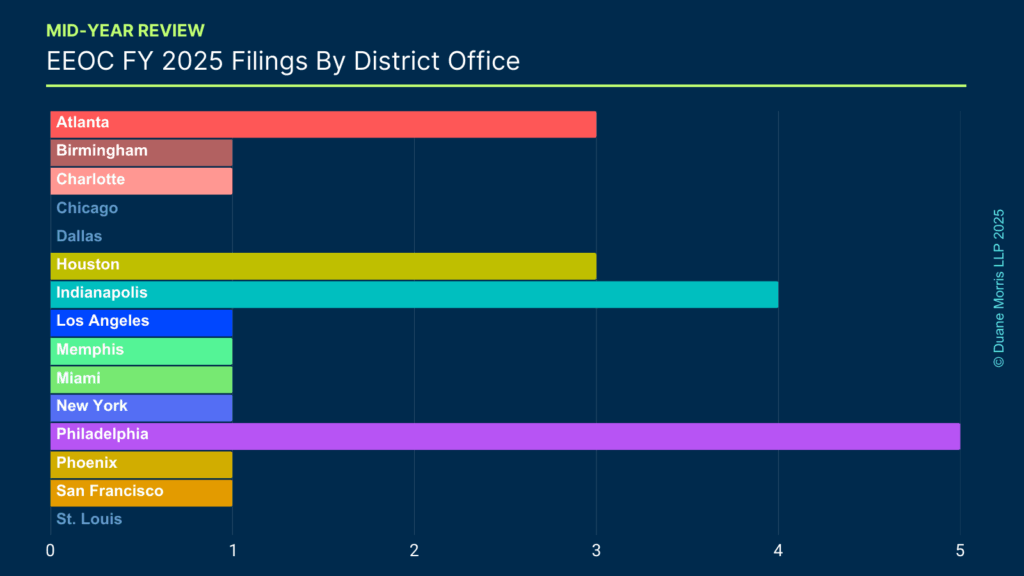

Cases Filed By EEOC District Offices

In addition to tracking the total number of filings, we closely monitor which of the EEOC’s 15 district offices are most active in terms of filing new cases over the course of the fiscal year. Some districts tend to be more aggressive than others, and some focus on different case filing priorities. The following chart shows the number of lawsuit filings by EEOC district office.

The most noticeable trend of the first six months of FY 2025 is that the Philadelphia District Office has already filed five lawsuits. Indianapolis has four lawsuit filings, and Atlanta and Houston have three each. Many of the district offices have yet to file a lawsuit at all in FY 2025. But for employers in the Philadelphia, Indianapolis, Atlanta, and Houston metropolitan areas, these early tea leaves suggest that a higher likelihood of pending charges may turn into federal lawsuits by September.

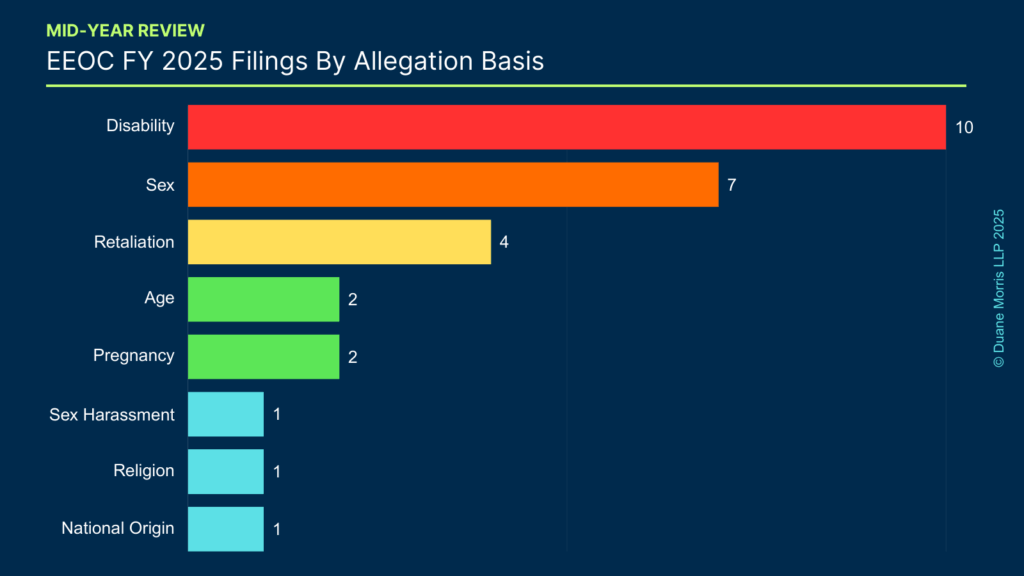

Analysis Of The Types Of Lawsuits Filed In First Half Of FY 2025

We also analyzed the types of lawsuits the EEOC filed throughout the first six months, in terms of the statutes and theories of discrimination alleged, in order to determine how the EEOC is shifting its strategic priorities. The chart below shows the EEOC filings by allegation type.

In the first half of FY 2025, 64% or 14 of the 22 filings contained Title VII claims. The percentage of each type of filing has remained fairly consistent over the past several years, until the first half of FY 2024, when nearly every filing contained Title VII claims, with 12 of the 14, or 87% alleging these violations. This year’s filings are more aligned with years prior to FY 2024. In FY 2023, Title VII claims comprised of 59% of all filings, 69% in FY 2022, and 62% in 2021. ADA cases were alleged in 10 or 45% of the lawsuits filed, a substantial increase from FY 2024, where ADA claims were only 21% of the cases in the first half of the year. There were also two ADEA lawsuits filed.

The graph set out below shows the number of lawsuits filed according to the statute under which they were filed (Title VII, Americans With Disabilities Act, Pregnancy Discrimination Act, Equal Pay Act, and Age Discrimination in Employment Act).

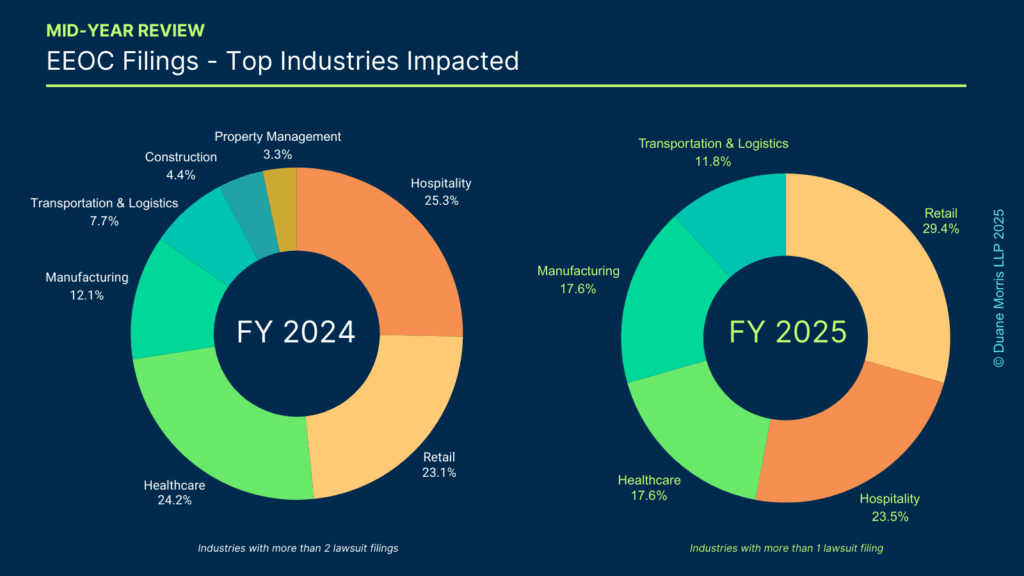

The industries impacted by EEOC-initiated litigation have also remained consistent in FY 2025. The chart below details that hospitality, healthcare, and retail employers have maintained their lead as corporate defendants in the last 18 months of EEOC-initiated litigation.

Notable 2025 Lawsuit Filings

Sexual Harassment

In EEOC v. Teamlyders LLC (E.D. Mich. Feb. 28, 2025), the EEOC filed an action against six entities operating Taco Bell restaurants in Michigan, alleging that a senior area manager subjected female employees, including multiple teenage employees, to sexual harassment. The EEOC contended that the harassment included inappropriate sexual comments, such as asking if underage employees were sexually active, asking an employee if she would give him “sugar” when she turned 18, unwanted and inappropriate touching of females under age 18, and asking an assistant manager for videos or images of her having sex with her boyfriend. The EEOC also asserted that the defendants failed to take effective action against the manager, despite receiving multiple complaints from different employees, supervisors, and managers, and that one female employee was terminated immediately after making a complaint about the manager’s conduct.

Sex / Disability Discrimination

In EEOC v. Equinox Holdings, Inc., Case No. 24-CV-3597 (D.D.C. Dec. 23, 2024), the EEOC brought suit alleging that the defendant, which owns and operates fitness facilities and gyms nationwide, illegally discriminated against a woman who suffers from endometriosis on the basis of disability and sex when it failed to hire her as a front desk associate at its sports club in Washington because of her “monthly cycle,” failed to provide her with a potential need for a reasonable accommodation, and failed to accommodate her disability during the job application process. The EEOC asserted that the applicant, who previously worked in similar positions for other gyms, asked for her second-round interview to be delayed by a few days because she experiences painful menstrual cramps and was anticipating being in that situation imminently. The EEOC alleged that the defendant rejected the applicant, and that the manager with whom she had her initial interview told her in a text message that she was passed over for the position because there was a concern that she would be absent in the future “due to [her] monthly cycle.” The EEOC also alleged Equinox subsequently hired a male applicant with no prior experience working in gyms for the front desk associate position.

Disability Discrimination

In EEOC v. Alto Experience, Inc., Case No. 24-CV-2208 (E.D. Va. Dec. 6, 2024), the EEOC filed an action alleging that the defendant, a ride hailing company, violated the ADA when it denied reasonable accommodations and employment to deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals who applied to work as personal drivers, despite the availability of technological accommodations, and, in some instances, despite previous experience as drivers for other ride-hailing companies. The EEOC also alleged that some qualified deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals who were denied accommodations or employment as personal drivers were steered into in less-desirable car washing positions.

These filings illustrate that the EEOC will likely continue to prioritize sex, sex harassment, and disability discrimination claims in the second half of FY 2025.

Release Of Enforcement Statistics

On January 17, 2025, the EEOC published its Fiscal Year 2024 Annual Performance Report (“FY 2024 APR”), summarizing the Commission’s recent year of enforcement activity and recovery on behalf of U.S. workers. As the Annual Performance Report highlights, 2024 was a successful year for the EEOC, and the Commission recovered nearly $700 million for 21,000 individuals (a 5% increase over FY 2023). Significantly, according to the Commission it successfully resolved 132 merits lawsuits (a 33% increase over FY 2023) and achieved a successful outcome in 128 (or 97%) of all suit resolutions. See FY 2024 APR at p. 12. Given the Commission’s spike in enforcement activity, and its odds of prevailing, the Annual Performance Report reminds employers of the risks associated with an EEOC lawsuit and the need maintain and administer EEOC-compliant employment policies.

FY 2024 Highlights

In the EEOC’s 78-page Annual Performance Report, the Commission discusses, at length, its annual performance results and the significant victories it achieved in FY 2024. Specifically, the Report highlights that the Commission secured nearly $700 million for U.S. workers, the highest monetary amount in recent history, including over $469 million for private sector and state/local government workers through mediation, conciliation, and settlements, as well as more than $190 million for federal workers. The EEOC also notes that it filed 111 new lawsuits in 2024 on behalf of alleged victims of workplace discrimination, several of which were brought under the newly enacted and untested Pregnant Workers Fairness Act (“PWFA”). FY 2024 APR at p. 2

The Commission also reported that it received 88,531 new charges of discrimination this past fiscal year, representing a 9% increase over FY 2023. The EEOC experienced increased demand from the public, handling over 553,000 calls through its agency contact center, and receiving over 90,000 emails, which represented a growing demand for the Commission’s services. Id. at p. 3. The Commission also made it clear that it would continue to focus on systemic enforcement, and in 2024 alone, it resolved 16 systemic cases and obtained 23.9 million on behalf of 4,074 victims of systemic discrimination, and other significant equitable relief. Id.

Takeaways For Employers

By many accounts, FY 2024 was a record-breaking year for the EEOC. As demonstrated in the report, the Commission has pursued an increasingly aggressive and ambitious litigation strategy to achieve its regulatory goals. The data confirms that the EEOC had a great deal of success in obtaining financially significant monetary awards.

We anticipate that the EEOC will continue to aggressively pursue its strategic priority areas in FY 2025. There is no reason to believe that the annual “September surge” is not coming, in what could be another precedent-setting year. However, with a new presidential administration, there are apt to be changes in the coming year. We will continue to monitor EEOC litigation activity on a daily basis, and look forward to providing our blog readers with up-to-date analysis on the latest developments.

Finally, as previously talked about on the blog here – we are thrilled to announce that will be providing a webinar on May 5, 2025, to further analyze the above data. Employers will gain insight on what they should be doing to ready themselves for the remainder of FY 2025. Save the date and stay tuned!