By Gerald L. Maatman, Jr. and Jennifer A. Riley

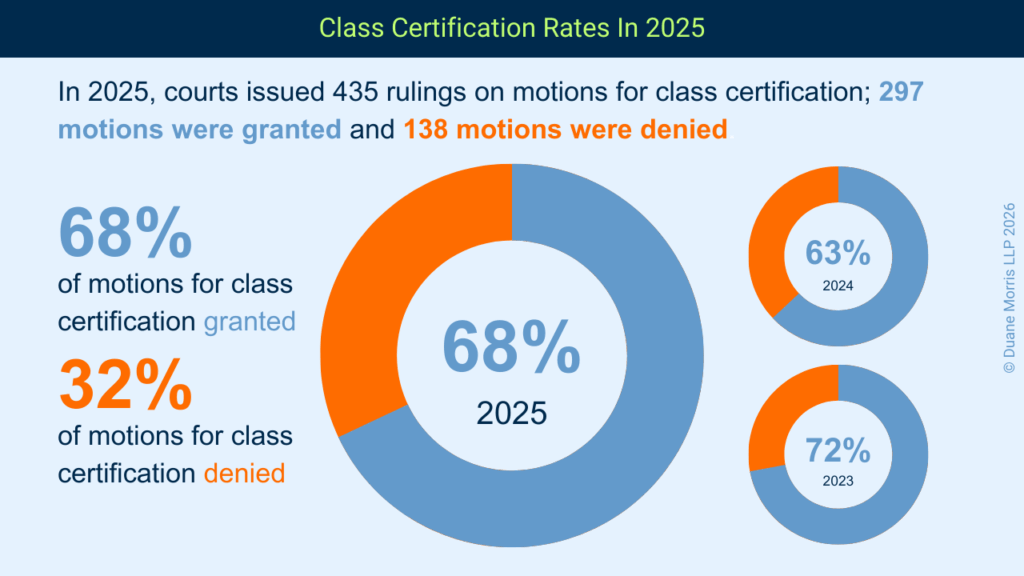

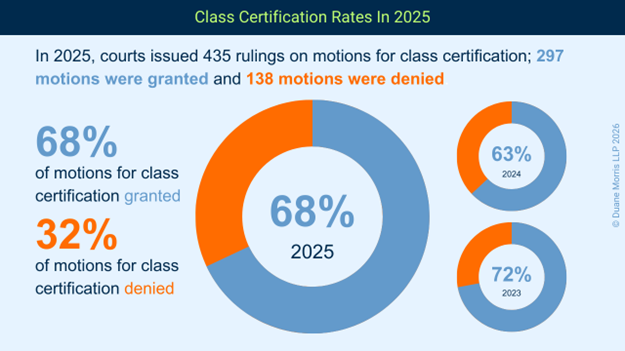

Duane Morris Takeaway: Although courts issued a similar number of decisions on motions for class certification in 2025 as compared to 2024, the plaintiffs’ class action bar obtained certification at a higher rate overall across all substantive areas, suggesting that plaintiffs are being more selective in their investments and the cases they pursue through class certification.

Watch Duane Morris partner Jennifer Riley discuss the certification rates in 2025 and what it means for 2026 in the video below:

Courts issued a similar number of decisions on motions for class certification in 2025, as compared to 2024, but the plaintiffs’ class action bar obtained certification at a higher rate overall.

Across all major areas of class action litigation in 2025, courts issued rulings on 435 motions for class certification. By comparison, in 2024, courts issued rulings on 432 motions for class certification, and, in 2023, court issued rulings on 451 motions for class certification.

In 2025, however, courts granted motions for class certification at a higher rate. Courts granted 297 motions for class certification in whole or in part, a rate of approximately 68%.

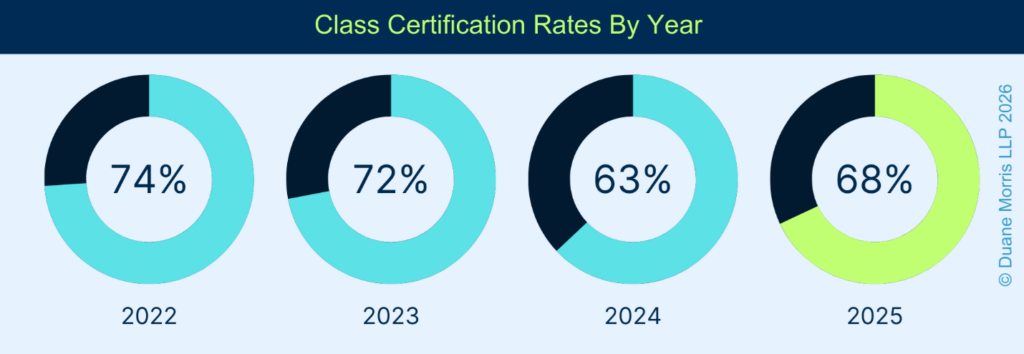

This number is higher than the percentage granted in 2024, where courts granted 272 motions for class certification, for a certification rate of approximately 63%, but on par with plaintiffs’ success rate in 2023. In 2023, courts granted 324 motions for class certification, for a certification rate of approximately 72%.

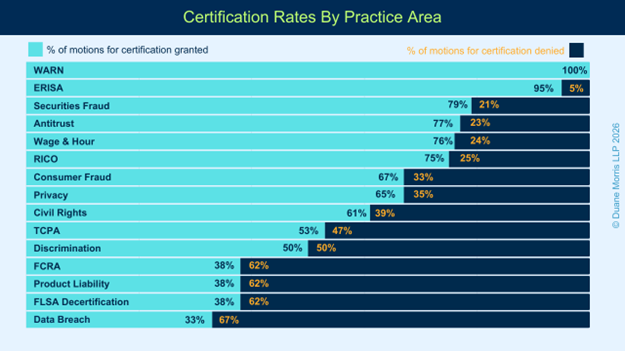

In 2025, plaintiffs also maintained more consistent certification rates across substantive areas, from a low of 33% in the data breach area, to highs above 70% in the antitrust, wage & hour, and securities fraud areas. Likewise, courts granted more than 90% of the motions for class certification that they adjudicated in 2025 in the ERISA and WARN areas.

Of these, plaintiff succeeded in obtaining or maintaining certification in 297 rulings, for an overall success rate of approximately 68%. Thus, although courts certified fewer classes in 2025, they granted certification at a higher rate as compared to 2024.

In 2024, plaintiffs succeeded in obtaining or maintaining certification in 272 rulings, an overall success rate of approximately 63%.

The success rate plaintiffs achieved in 2025 is closer to the rates of certification in 2022 and 2023. In 2023, courts issued rulings on 451 motions to grant or deny class certification, and plaintiffs succeeded in obtaining or maintaining certification in 324 rulings, with an overall success rate of 72%. In 2022, courts issued rulings on 335 motions to grant or to deny class certification, and plaintiffs succeeded in obtaining or maintaining certification in 247 rulings, an overall success rate of nearly 74%.

In 2025, the number of motions that courts considered and the number of rulings they issued varied significantly across substantive areas. The following summarizes the results in each of ten key areas of class action litigation (sorted by plaintiffs’ success rate):

- WARN Act Class Actions: 100% granted (5 of 5 granted / 0 of 5 denied)

- ERISA Class Actions: 95% granted (18 of 19 granted / 1 of 19 denied)

- Securities Fraud Class Actions: 79% granted (26 of 33 granted / 7 of 33 denied)

- Antitrust Class Actions: 77% granted (17 of 22 granted / 5 of 22 denied)

- Wage & Hour Class/ Collective: 76% granted (103 of 135 granted / 32 of 135 denied)

- RICO Class Actions: 75% granted (6 of 8 granted / 2 of 8 denied)

- Privacy Class Actions: 67% granted (8 of 12 granted / 4 of 12 denied)

- Consumer Fraud Class Actions: 66% granted (34 of 51 granted / 17 of 51 denied)

- FLSA Decertification: 62% denied (8 of 13 denied / 5 of 13 granted)

- Civil Rights Class Actions: 61% granted (48 of 79 granted / 30 of 79 denied)

- TCPA Class Actions: 53% granted (10 of 19 granted / 9 of 19 denied)

- Discrimination Class Actions: 50% granted (10 of 20 granted / 10 of 20 denied)

- Products Liability Class Actions: 38% granted (3 of 8 granted / 5 of 8 denied)

- FCRA Class Actions: 38% granted (3 of 8 granted / 5 of 8 denied)

- Data Breach Class Actions: 33% granted (1 of 3 granted / 2 of 3 denied)

The plaintiffs’ class action bar obtained high rates of success on motions for class certification across most substantive areas in 2025. Plaintiffs obtained the highest rates of success in class actions asserting violations of the WARN Act, the ERISA, and the RICO, followed closely by wage & hour and securities fraud.

In cases where plaintiffs alleged claims for violation of the WARN Act, plaintiffs succeeded in certifying classes in all five of the rulings they obtained during 2025, a success rate of 100%. In 2024, by contrast, plaintiffs prevailed in six of seven rulings, a success rate of 85.7%.

In ERISA class actions, plaintiffs succeeded in obtaining orders granting certification in 18 of the 19 rulings issued during 2025, a success rate of 95%. In cases alleging RICO violations, plaintiffs succeeded in obtaining orders certifying classes in 6 of 8 rulings during 2025, a success rate of 75%. In 2024, by contrast, plaintiffs achieved a lower rate of success in both areas. In ERISA litigation, plaintiffs prevailed on 24 of 36 motions for class certification, for a success rate of 66.6%, and, in cases alleging RICO violations, plaintiffs prevailed on only two of six motions for class certification in 2024, a success rate of 33.3%.

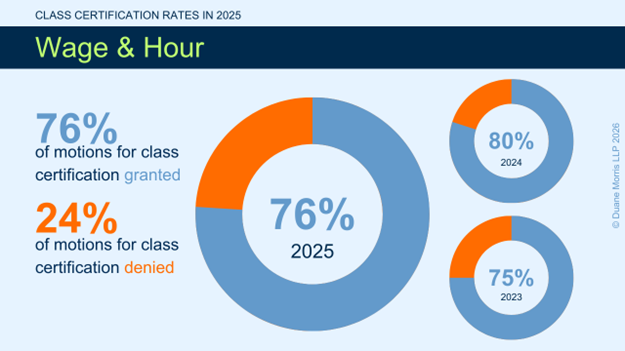

In wage & hour class and collective actions, plaintiffs succeeded in obtaining orders granting certification in 103 of the 135 rulings issued during 2025, a success rate of 76%. In securities fraud class actions, plaintiffs succeeded in certifying classes in 26 of 33 rulings issued during 2025, a success rate of 79%. These numbers are on par with plaintiffs’ rates of success in 2024. In 2024, plaintiffs succeeded on 124 of 156 motions for certification of wage & hour class and collective actions, a success rate of 79%, and on 19 of 27 motions for class certification in securities fraud matters, a success rate of 70%.

As noted above, the overall certification rate was higher in 2025, moving from 63% in 2024 to 68% in 2025, but plaintiffs also fared better across substantive areas. Plaintiff succeeded in certifying classes at a rate greater than 50% across all substantive areas except discrimination (50%), products liability (38%), FCRA (38%), and data breach (33%). By contrast, in 2024, plaintiffs fell short of that benchmark in data breach (50%), products liability (50%), privacy (45%), civil rights (40%), FCRA (38%), TCPA (38%), and RICO (33%).

- Courts Issues More Rulings In FLSA Collective Actions Than In Any Other Area Of Law

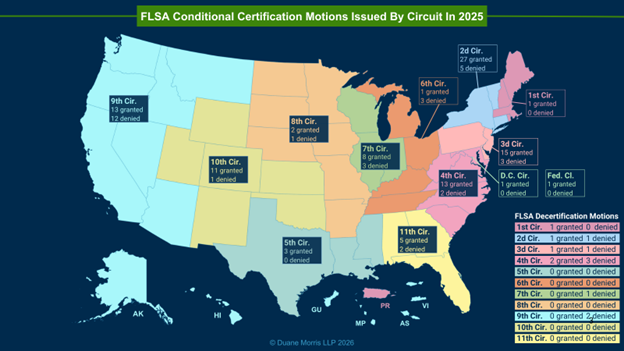

In 2025, courts condintued to issue more certification rulings in FLSA collective actions than in any other type of complex litigation area. Many courts historically have applied a two-step process in the FLSA context that allows a plaintiff to obtain an order granting “conditional” certification early in the proceeding with a modest showing. This standard allows plaintiffs to increase the size of their cases with comparatively low investment, contributing to the number of filings in this area. In 2025, courts considered more motions for certification in FLSA matters than in any other substantive area. Overall, courts issued 148 rulings. Of these, 135 addressed motions for conditional certification of collective actions, and 13 addressed motions for decertification of conditionally certified collective actions. Of the 135 conditional certification rulings, 103 granted conditional certification, for a success rate of over 76%.

While plaintiffs’ success rate has remained steady over the past few years, the number of rulings has declined.

In 2024, courts issued 171 rulings on motions for certification. Of these, 156 addressed motions for conditional certification of collective actions, and 15 addressed motions for decertification of conditionally certified collective actions. Of the 156 rulings that courts issued on motions for conditional certification, 124 rulings favored plaintiffs, for a success rate of 79.5%.

In 2023, courts issued 183 rulings on motions for certification. Of these, 165 addressed motions for conditional certification of collective actions, and 18 addressed motions for decertification of conditionally certified collective actions. Of the 167 rulings that courts issued on motions for conditional certification, 125 rulings favored plaintiffs, for a success rate of nearly 75%.

In 2022, courts issued 236 rulings on motions for certification. Of these, 219 addressed motions for conditional certification of collective actions, and 18 addressed motions for decertification of conditionally certified collective actions. Of the 219 rulings that courts issued on motions for conditional certification, 180 rulings favored plaintiffs, for a success rate of 82%.

The likely reason for this drop is the prevalence of arbitration agreements with class action and collective action waivers. Such arbitration agreements cause a depression in the numbers because: (i) some plaintiffs’ lawyers will bypass the court system altogether and proceed with claims in arbitration; or (ii) for those that file lawsuits, a significant percentage are thrown out of court based on motions to compel arbitration filed by the defendant.

The decline in the number of rulings on motions for conditional certification from 236 in 2022, to 135 in 2025, represents a decrease of 43%. This phenomenon reflects the impact of the shifting standards by which courts are adjudicating such motions.

Until 2021, courts almost universally applied a two-step process to certification of FLSA collective actions. At the first stage, courts required a plaintiff to make only a “modest factual showing” that he or she is similarly situated to others. Plaintiffs often met that burden at the outset of litigation by submitting declarations from themselves and/or a limited number of potential collective action members, and courts then authorized them to send notice of the lawsuit to potential opt-in plaintiffs. At the second stage, courts conducted a more thorough examination of the evidence to determine whether, with the benefit of discovery, a plaintiff demonstrated that he or she in fact is similarly-situated to others and the court manageably can try the case on a collective basis.

Over the past five years, however, courts have revisited the two-step process and considered whether it comports with the plain language of the FLSA. Federal appellate courts in three circuits – the Fifth Circuit, the Sixth Circuit, and the Seventh Circuit – along with various district courts – have answered that question in the negative.

In 2021, the Fifth Circuit in Swales, et al. v. KLLM Transport Services, LLC, 985 F.3d 430, 436 (5th Cir. 2021), rejected the two-step approach to evaluating motions for certification of collective actions. The Fifth Circuit held instead that district courts should “rigorously scrutinize the realm of ‘similarly-situated’ workers … at the outset of the case.”

In 2023, the Sixth Circuit in Clark v. A&L Homecare & Training Center, LLC, 68 F.4th 1003 (6th Cir. 2023), likewise jettisoned the two-step approach but expressly declined to adopt the standard approved by the Fifth Circuit. Instead, the Sixth Circuit introduced a new standard that requires the plaintiff to demonstrate a “strong likelihood” that other employees are “similarly-situated” to the plaintiff.

In 2025, the Seventh Circuit in Richards v. Eli Lilly & Co., 149 F.4th 901 (7th Cir. 2025), rejected the two-step process but declined to go as far as Clark or Swales. Instead, the Seventh Circuit required the plaintiff to demonstrate a genuine dispute as to whether proposed collective action members are similarly-situated, noting that a defendant “must be permitted to submit rebuttal evidence” for the court to consider.

Although encompassing different standards, Swales, Clark, and Richards require plaintiffs to make a more substantial showing than the first step of the two-step approach entails, thereby requiring more factual development and, as a result, more investment on the part of the plaintiffs’ bar.

As a result, filings have shifted. Plaintiffs filed fewer wage & hour lawsuits (and hence brought fewer certification motions) in the Fifth and Sixth Circuits over the past two years, as plaintiffs shifted their efforts away from pursuing collective actions in the Fifth and Sixth Circuits. As a result of Richards, plaintiffs likely will shift their efforts away from pursuing collective actions in the Seventh Circuit over the upcoming year.

In 2025, courts in the Fifth Circuit, issued rulings on three motions for conditional certification, and plaintiffs prevailed on all of them, for a success rate of 100% and, in the Sixth Circuit, courts issued rulings on three motions for conditional certification, and plaintiffs prevailed on only one, for a success rate of 33% Similarly in 2024, courts in the Fifth Circuit issued rulings on six motions for conditional certification, and plaintiffs prevailed on five, for a success rate of 83%, and, in the Sixth Circuit, courts issued rulings on ten motions for conditional certification, and plaintiffs prevailed on eight, for a success rate of 80%.

While the results continued to be solid for plaintiffs, the investment of time and effort to secure certification has deterred plaintiffs from filing in these circuits. By way of example, in 2022, the last full year before Clark, courts in the Sixth Circuits issued 36 decisions on motions for conditional certification.

In 2023, as Clark began to take hold, courts in the Sixth Circuit issued 22 decisions on motions for conditional certification. In 2024, the first full year after Clark, courts issued rulings on ten motions for conditional certification, and, in 2025, courts in the Sixth Circuit issued rulings on only three motions for conditional certification, reflecting a 92% decline in just four years.

These numbers may continue to shift and decline as plaintiffs shift their case filings to other circuits that have retained the lenient two-step approach or, as more courts revisit the standards applicable to certification, shift their case filings to other areas.

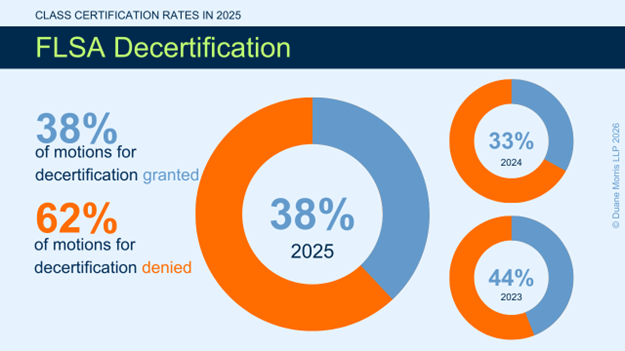

At the decertification stage, courts generally have conducted a closer examination of the evidence and, as a result, defendants historically have enjoyed an equal if not higher rate of success on these second-stage motions as compared to plaintiffs. The results in 2025, however, were less favorable for defendants. Courts issued 13 rulings on motions for decertification. Of these, five favored defendants, for a success rate of 38%, and eight rulings favored plaintiffs, for a success rate of 62%.

In 2022, 2023, and 2024, by comparison, courts issued more rulings on motions for decertification. In 2024, courts issued 15 rulings, five of which favored defendants, for a success rate of only 33.3%, and 10 of which favored plaintiffs, for a success rate of 66.6%. In 2023, courts issued 18 rulings on motions for decertification.

Of these, eight favored defendants, for a success rate of 44.4%, and ten rulings favored plaintiffs, for a success rate of 55.6%. In 2022, courts similarly issued 18 rulings on motions for decertification. Defendants prevailed in nine, for a success rate of 50%, and plaintiffs prevailed in nine, for a success rate of 50%.

Implications: The decrease in rulings on motions for decertification likely flows from the decrease in rulings on motions for conditional certification, as well as the decrease in the number of courts applying the traditional two-step certification model. If more courts abandon the traditional two-step certification process, and thereby increase the time and expense required to gain a certification order, the number of decertification rulings likely will continue to decrease.