By Gerald L. Maatman, Jr. and Jennifer A. Riley

Duane Morris Takeaway: Of all defenses, a defendant’s ability to enforce an arbitration agreement containing a class or collective action waiver may have had the single greatest impact in terms of shifting the pendulum of class action litigation. With its decision in Epic Systems Corp. v. Lewis, et al., 138 S. Ct. 1612 (2018), the U.S. Supreme Court cleared the last hurdle to widespread adoption of such agreements. In response, more companies of all types and sizes updated their onboarding materials, terms of use, and other types of agreements to require that employees and consumers resolve any disputes in arbitration on an individual basis. To date, companies have enjoyed a high rate of success enforcing those agreements and using them to thwart class actions out of the gate.

Watch below as Duane Morris partner Jerry Maatman discusses the arbitration defense and how it impacted class action litigation in 2023.

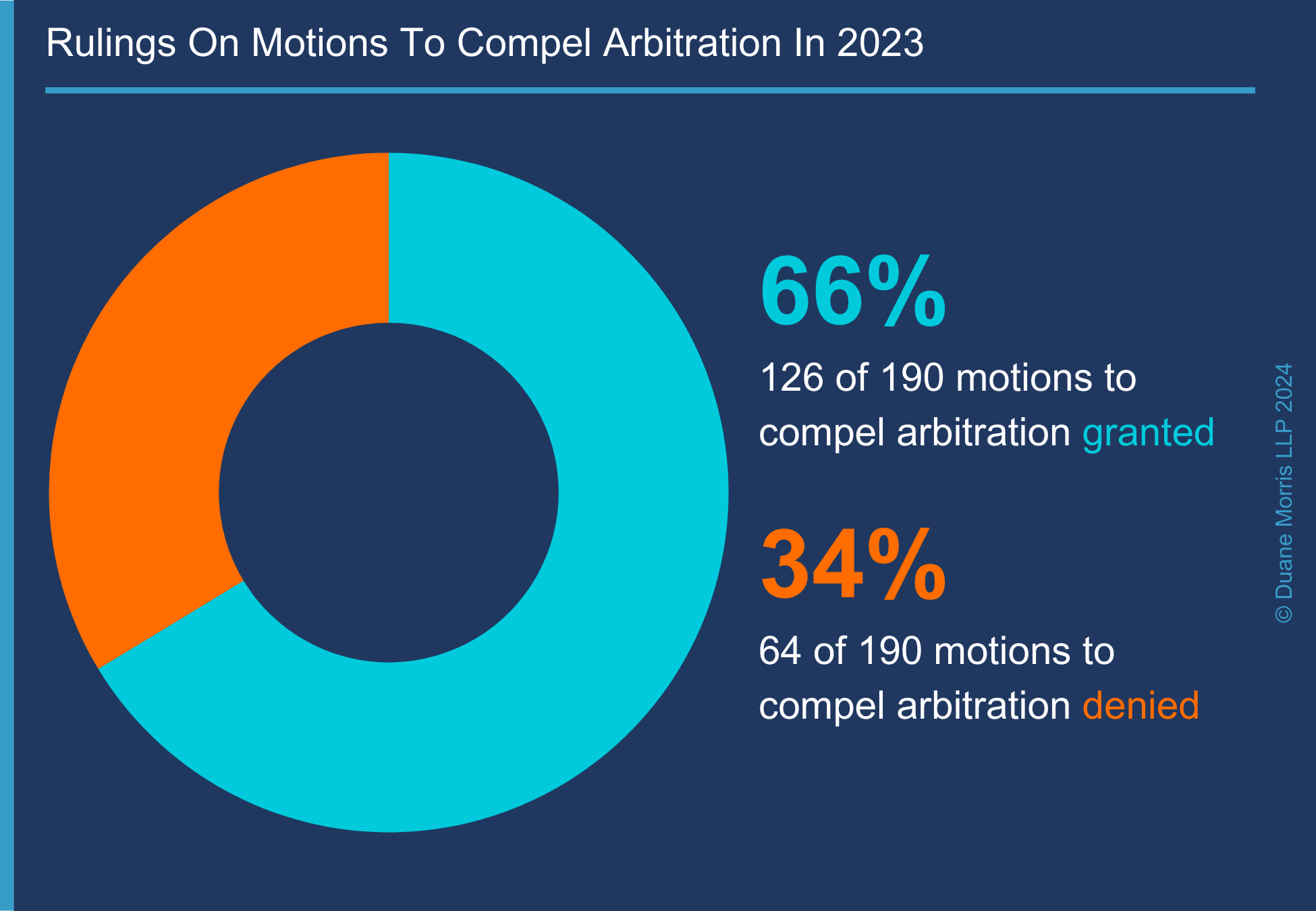

Statistically, corporate defendants fared well in asserting the defense. Across various areas of class action litigation, the defense won approximately 66% of motions to compel arbitration (approximately 123 motions across 187 cases) over the past year. Such numbers are similar to the numbers we saw in 2022, where defendants succeeded on 67% of motions to compel arbitration (roughly 64 motions granted in 96 cases).

The following graph shows this trend:

Despite a tumultuous year in 2022, the arbitration defense in 2023 remained one of the most powerful weapons in the defense toolkit in terms of avoid class and collective actions.

In 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court limited application of the FAA to workers who participate in interstate transportation and, perhaps more significantly, on the legislative front, Congress significantly limited the availability of arbitration for cases alleging sexual harassment or sexual assault. Congress passed the Ending Forced Arbitration of Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment Act (the Ending Forced Arbitration Act or EFAA), and President Biden signed the Act into law on March 3, 2022.

The EFAA amended the FAA and provided plaintiffs the discretion to enforce pre-dispute arbitration provisions in cases where they allege conduct constituting “a sexual harassment dispute or a sexual assault dispute” or are the named representatives in “a class or in a collective action alleging such conduct.” In other words, the Act did not render such agreements invalid, but allowed the party bringing the sexual assault or sexual harassment claims to elect to enforce them or to avoid them.

It is likely that defendants have not yet felt the impact of either development.

- The Impact Of The EFAA

Despite this setback for the arbitration defense in 2022, companies continued to enjoy a high rate of success enforcing these agreements and using them to thwart class actions in 2023. Since the EFAA became effective on March 3, 2022, courts have issued only 34 published decisions on plaintiffs’ attempts to use the EFAA to avoid arbitration. Plaintiffs succeeded in enforcing the EFAA and keeping claims in court, in whole or in part, in only about 9 of those rulings.

Many of the decisions denying enforcement of the EFAA turned on the fact that the EFAA is not retroactive. Congress provided that the provisions of the Ending Forced Arbitration Act would “apply with respect to any dispute or claim that arises or accrues on or after the date of enactment of this Act [March 3, 2022].” Thus, although courts have disagreed as to when disputes or claims “arise or accrue” for purposes of the EFAA, in many cases, all potential dates pre-dated March 3, 2022, and, therefore, courts concluded that the Act did not apply.

Many courts recognized an exception in cases where plaintiffs were able to allege a “continuing violation” that extended past March 3, 2022, generally finding that the EFAA allowed such claims to remain in court. In Betancourt, et al. v. Rivian Automotive, No. 22-CV-1299, 2023 WL 5352892, at *1 (C.D. Ill. Aug. 21, 2023), for example, plaintiff filed a class action lawsuit alleging that she was regularly subjected to unwanted sexual advances during her employment from December 6, 2021, through “about June 1, 2022,” and, despite making reports to several supervisory level employees, defendant failed to remedy the conduct. The defendant invoked its arbitration agreement with the plaintiff, which included a class and collective action waiver, and the plaintiff claimed that the agreement was unenforceable due to the EFAA. Id. at *2. Acknowledging that the EFFA does not apply retroactively, the court considered whether the action accrued before March 3, 2022, and held that it did not. The court reasoned that the plaintiff alleged a continuing violation, which was ongoing on the date the EFAA was enacted, and, therefore, the arbitration agreement and class action waiver were unenforceable. Id. at *5.

Approximately 12 of the decisions turned on court interpretations regarding the scope of the EFAA, and we observed the beginnings of a patchwork quilt of interpretations as to the scope of the claims subject to the EFFA. In Johnson, et al. v. Everyrealm, Inc., 657 F. Supp. 3d 535 (S.D.N.Y. 2023), for instance, the plaintiff brought claims for race discrimination, pay discrimination, sexual harassment, retaliation, and intentional infliction of emotional distress, among other things, and the defendant moved to dismiss the sexual harassment claim and to compel arbitration of the remainder. The court denied the motion. It noted that, in its operative language, the EFAA makes a pre-dispute arbitration agreement invalid and unenforceable “with respect to a case which is filed under Federal, Tribal, or State law and relates to the . . . sexual harassment dispute.” Id. at 558 (quoting 9 U.S.C. § 402(a) (emphasis added)). It found such text “clear, unambiguous, and decisive as to the issue.” Id. As a result, the district court concluded that plaintiff pled a plausible claim of sexual harassment in violation of New York law and “construe[d] the EFAA to render an arbitration clause unenforceable as to the entire case involving a viably pled sexual harassment dispute, as opposed to merely the claims in the case that pertain to the alleged sexual harassment.” Id. at 541.

In Mera, et al. v. SA Hospitality Group, LLC, No. 1:23 Civ. 03492 (S.D.N.Y. June 3, 2023), by contrast, plaintiff brought claims for unpaid wages under the FLSA and the New York Labor Law (NYLL), as well as claims for sexual orientation discrimination and hostile work environment. The employer moved to compel arbitration, and the court found the agreement unenforceable as to his hostile work environment claims but enforceable as to his FLSA and NYLL claims. The plaintiff argued that, under the EFAA, the arbitration agreement was unenforceable as to his entire “case,” including his unrelated wage and hour claims under the FLSA and the NYLL, which he brought on behalf of a broad group of individuals. Id. at *3. The court disagreed. It held that, under the EFAA, an arbitration agreement executed by an individual alleging sexual harassment is unenforceable only with respect to the claims in the case that relate to the sexual harassment dispute, since “[t]o hold otherwise would permit a plaintiff to elude a binding arbitration agreement with respect to wholly unrelated claims affecting a broad group of individuals having nothing to do with the particular sexual harassment affecting the plaintiff alone.” Id.

- The Impact Of The Transportation Worker Exemption

Despite the U.S. Supreme Court’s clarification of the transportation worker exemption to the FAA in 2022, lower courts continue to grapple and disagree about its scope, effectively holding a potential wave of workplace litigation against transportation, logistics, and delivery companies in check.

In the first and arguably the largest door-opener to the courthouse for the plaintiffs’ class action bar during 2022, the Supreme Court narrowed the application of the Federal Arbitration Act by expanding its so-called “transportation worker exemption” in Southwest Airlines Co. v. Saxon, 142 S.Ct. 1783 (2022). The plaintiff, a ramp supervisor, brought a collective action lawsuit against Southwest for alleged failure to pay overtime. Id. at 1787. Southwest moved to enforce its workplace arbitration agreement under the FAA. In response, the plaintiff claimed that she belonged to a class of workers engaged in foreign or interstate commerce and, therefore, fell within §1 of the FAA, which exempts “contracts of employment of seamen, railroad employees, or any other class of workers engaged in foreign or interstate commerce.” Id. The Supreme Court granted review and went on to hold that “any class of workers” directly involved in transporting goods across state or international borders falls within the exemption. Id. at 1789. It had no problem finding the plaintiff part of such a class: “We have said that it is ‘too plain to require discussion that the loading or unloading of an interstate shipment by the employees of a carrier is so closely related to interstate transportation as to be practically a part of it.’ . . . We think it equally plan that airline employees who physically load and unload cargo on and off planes traveling in interstate commerce are, as a practical matter, part of the interstate transportation of goods.” Id. (citation omitted).

Despite this decision clarifying the exemption, lower courts remained steeped in disputes, often generating irreconcilable differences of opinion over which workers signed arbitration agreements enforceable under the FAA and which did not. In Fraga v. Premium Retail Services, Inc., No. 1:21-CV-10751, 2023 WL 8435180 (D. Mass. Dec. 5, 2023), for example, after the parties litigated the enforceability of the arbitration agreement for more than two years, and the dispute resulted in three full scale judicial opinions, a two-day evidentiary hearing with 6 witnesses, and hundreds of pages of exhibits, the court determined that the plaintiff’s work, which involved sorting, loading, and transporting materials to retailers located within or outside Massachusetts “was not performed frequently and was not closely related to interstate transportation” so as to bring him within the exemption. Id. at *6.

Similarly, in Nunes, et al. v. LaserShip, Inc., No. 1:22-CV-2953, 2023 WL 6326615 (N.D. Ga. Sept. 28, 2023), the plaintiffs opposed a motion to compel arbitration contending that last-mile delivery drivers are engaged in interstate commerce because the goods they transport have traveled interstate and remain in the stream of commerce until delivered. The court disagreed. Whereas it found “no doubt” that the plaintiffs belong to a “class of workers employed in the transportation industry” because they locally transported packages from a warehouse to commercial and residential buildings, it concluded that plaintiffs “do not actually engage in interstate commerce.” Rather, their job entailed sorting and loading packages from the local warehouse and delivering the goods locally. Thus, the court determined that the plaintiffs were “too far removed from interstate activity,” and did not fall within § 1’s exemption.

By contrast, in Webb, et al. v. Rejoice Delivers, 2023 WL 8438577 (N.D. Cal. Dec. 5, 2023), the court found the opposite. The plaintiff picked up packages from local Amazon facilities and delivered the packages locally. The court, however, noted that, before reaching the local Amazon facilities, the goods had been ordered from Amazon’s website and taken to the local facilities by shipping trucks. As a result, the court held that, because plaintiff “pick[ed] up packages that ha[d] been distributed to Amazon warehouses, certainly across state lines, and transport[ed] them for the last leg of the shipment to their destination,” his work was “a part of a continuous interstate transportation” of goods, so that he was engaged in interstate commerce for the purposes of the FAA § 1 exemption. Id. at *7.

The U.S. Supreme Court is poised to offer more clarity as to this issue in Bissonnette, et al. v. LePage Bakeries Park St., LLC, No. 23-51 (U.S. Sept. 29, 2023). On September 29, 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court granted certiorari in to address the exemption. In Bissonnette, two workers who delivered breads and cakes sued a bakery claiming that it misclassified them as independent contractors and, therefore, denied them minimum wage and overtime. The workers asserted that the transportation worker exemption applied because they handled goods traveling in interstate commerce, but the Second Circuit affirmed the district court’s ruling granting defendant’s motion to compel arbitration.

The question presented to the U.S. Supreme Court involves whether, to be exempt from the FAA, a class of workers actively engaged in interstate transportation also must be employed by a company in the transportation industry. Thus, the Supreme Court’s ruling could provide additional clarity in narrowing or expanding the scope of the exemption, potentially opening the doors to additional class claims.

Given the impact of the arbitration defense, in 2024, companies are apt face additional hurdles, on the judicial or the legislative front, as the plaintiffs’ bar continues to look for workarounds. In particular, as more plaintiffs can assert claims that post-date the EFAA, we expect to see additional litigation and more decisions over the interpretation of the EFAA, including whether the Act’s use of the word “case” renders the statute applicable to all claims in the case, including claims other than sexual harassment and sexual assault, and whether the statute, therefore, will allow for a broader shield to the arbitration defense.

That said, the future viability of the arbitration defense remains an open question, as advocacy groups, government regulators, and political figures push for a ban on class action waivers in arbitration.