By Gerald L. Maatman, Jr. and Jennifer Riley

By Gerald L. Maatman, Jr. and Jennifer Riley

Duane Morris Takeaway: Over the past year, the Biden Administration continued to roll out changes on several fronts as it aimed to expand the rights, remedies, and procedural avenues available to workers. During 2022, such efforts fueled litigation. With its decision in West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency, 142 S.Ct. 2587 (2022), the U.S. Supreme Court imposed another hurdle to agency rule-making. Meanwhile, government enforcement litigation activity took a back seat.

Over the past two years, the U.S. Department of Labor, in particular, has continued to roll out worker-friendly rules that could have a cascading impact on workplace class actions, including rules designed to wipe out the pro-business policies of the Trump Administration. Such efforts continued on multiple fronts in 2022, including with respect to rules regarding businesses’ utilization of independent contractors and their use of the tip credit.

As to the former, effective January 6, 2021, the DOL during the Trump Administration adopted an Independent Contractor Rule that addressed the circumstances under which a worker qualifies as an independent contractor. The Rule arguably made it easier for companies, including companies operating in the gig economy, to utilize independent contractors. Although the DOL under the Biden Administration withdrew the Rule in May 2021, in March 2022, a federal district court in Texas found the DOL’s withdrawal of the Rule unlawful. Although the DOL appealed the decision in May 2022, it later abandoned the appeal and, instead, on October 13, 2022, the DOL issued a proposed new rule on independent contractor status. It described the proposed framework as “more consistent with longstanding judicial precedent” and stated that the DOL “believes the new rule [will] preserve essential worker rights and provide consistency for regulated entities.” The rule is likely to fuel further litigation in 2023 and have a cascading impact on the workplace class action landscape as it impacts litigation and potential recoveries.

The DOL’s efforts to regulate use of the tip credit have met similar controversy. The FLSA, at 29 U.S.C. § 203(m), permits an employer to use the tips received by tipped workers to satisfy a portion of its minimum wage obligation. In 1988, however, the DOL added a rule (the 80/20 Rule) to its Field Operations Handbook that purported to require employers to pay employees at the full minimum wage rate for time spent performing non-tip-producing tasks that exceeded 20% of their workweek. Multiple courts attempted to apply this guidance so as to require employers to separate tasks performed by tipped workers into categories of tip-producing, non-tip-producing, and unrelated tasks, and the ensuring litigation over these issues has plagued the hospitality industry, in particular, over the past decade.

In November 2018, the DOL under the Trump Administration issued an opinion letter withdrawing the 80/20 Rule and, in February 2019, it amended the Field Operations Handbook to include a “reasonable time” standard, explaining that “an employer of an employee who has significant non-tip related duties which are inextricably intertwined with [his or her] tipped duties should not be forced to account for the time that employee spends doing those intertwined duties.” In December 2020, the DOL issued the Tip Regulations Final Rule. After twice delaying the effective date of the Final Rule, on October 23, 2021, the DOL under the Biden Administration withdrew and replaced the Final Rule. In doing so, the DOL resurrected the 80/20 Rule and purported to limit the tip credit to non-tip-producing work that directly supports tip-producing work and does not exceed “a continuous period” of 30 minutes. The new rule went into effect on December 28, 2021. In 2022, the Restaurant Law Center and Texas Restaurant Association filed suit seeking to invalidate the new final rule. On February 22, 2022, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas denied their much-watched emergency motion seeking to enjoin nationwide enforcement of the new final rule but did not issue a ruling on the merits, and the appeal remains pending in the Fifth Circuit. The results are apt to fuel additional litigation in 2023.

The ultimate result is apt to elucidate the limits of agency rule-making authority and test the impact of the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent ruling in West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency, 142 S.Ct. 2587 (2022). In that case, the Supreme Court considered the validity of the Environmental Protection Agency’s new Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) Rule that was promulgated under Clean Air Act (CAA). It held that, under the major questions doctrine, the agency must point to “clear congressional authorization” for the authority it claims. The government failed to offer such authorization, instead pointing to a “vague statutory grant” that the Supreme Court found “not close to the sort of clear authorization required by our precedents.” Id. at 2614.

The changing tide of the Biden Administration’s policies has been slow to impact other areas. Whereas the DOL acted swiftly to reverse course on many fronts, over most of the past year, the EEOC continued to operate with a Trump-appointed majority of commissioners.

During 2022, however, the EEOC continued to operate with a Trump-appointed majority of commissioners. Although President Biden quickly named two Democrats for the five-member Commission, Charlotte E. Burrows and Jocelyn Samuels, as Chair and Vice Chair, respectively, the commission retained a Republican-appointed majority until former chair Janet Dhillon’s resignation on November 18, 2022. Although such expiration opened the door to a Democratic-appointed majority, the Senate has not yet confirmed a replacement.

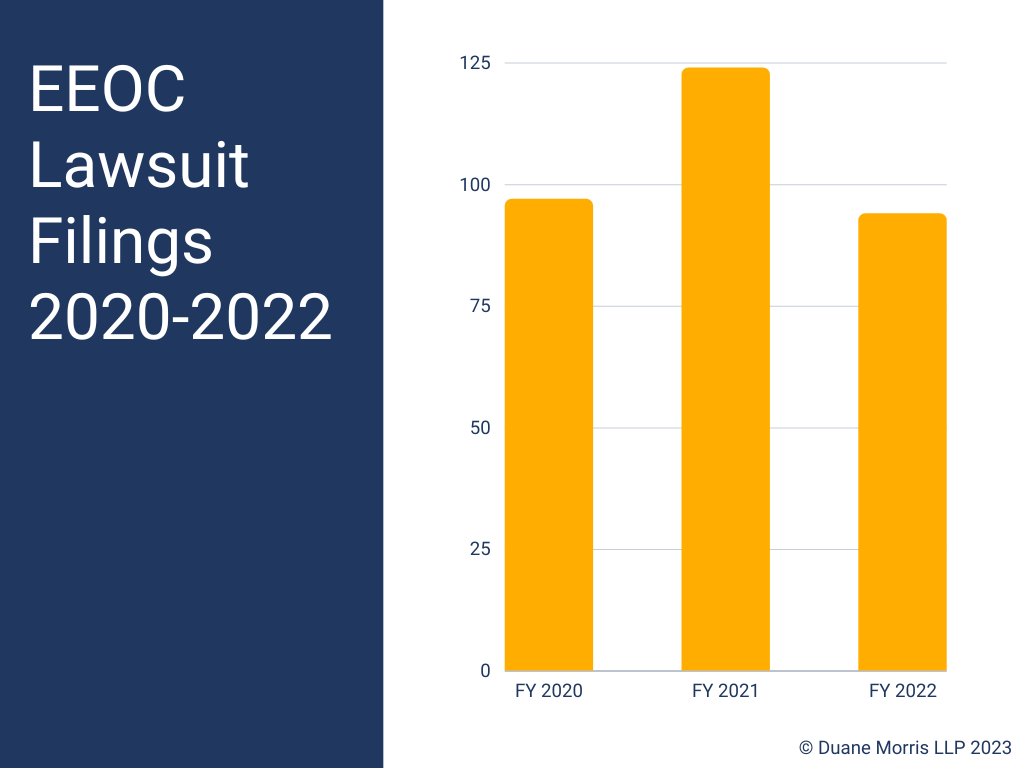

As the DOL continued efforts to work an about-face on the rule-making front, the EEOC’s year-over-year activity remained fairly steady. During fiscal year 2022, the EEOC filed 94 lawsuits. The EEOC’s year-over-year activity remained fairly steady. During fiscal year 2022, the EEOC filed 94 lawsuits, including 92 merits lawsuits and two subpoena enforcement actions. This number marked a significant decrease from the filings during fiscal year 2021, when the EEOC filed 124 lawsuits, including 116 merits lawsuits. This year’s filing data more closely resembles fiscal year 2020, when the EEOC filed 97 total lawsuits, including 93 merits lawsuits.

Notably, the EEOC’s California district offices in San Francisco and Los Angeles combined for 13 filings this past year, which is identical to the combined 13 cases they filed in fiscal year 2021.

According to the EEOC, it filed 13 systemic lawsuits this past year, the same number it filed during fiscal year 2021. The EEOC reported that it has 29 pending systemic cases, which accounted for 16% of the EEOC’s docket in fiscal year 2021. This data has not yet been published for fiscal year 2022.

In contrast, by the end of FY 2018, the EEOC had 71 systemic cases on its active docket, two of which included over 1,000 victims, and systemic cases accounted for 23.5% of its active lawsuits in that year, likely reflecting a stalling in the ability of its Democratic-appointment members to push this aspect of the EEOC’s agenda.

Comparing its monetary recovery to previous years, the EEOC recovered $535.5 million in all types of cases in FY 2020, $486 million in FY 2019, and $505 million in FY 2018.

In sum, whereas companies continued to see pro-business rules promulgated by the Trump Administration withdrawn and overwritten in 2022, courts continued to impose hurdles to agency rulemaking, the success of which will continue to be seen in 2023. Enforcement activity remained steady as political appointments remain pending.

Employers are apt to see increased activity in 2023 as the EEOC in particular gains its full component of Biden appointees and can exercise its majority power to advance its agenda.