By Gerald L. Maatman, Jr. and Jennifer A. Riley

By Gerald L. Maatman, Jr. and Jennifer A. Riley

Duane Morris Takeaway: In 2022, actions under the California Private Attorneys General Act (PAGA), Cal. Lab. Code, §§ 2698, et seq., saw their first setback as the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Viking River Cruises, Inc. v. Moriana, et al., 142 S.Ct. 1906 (2022), created a workaround to arbitration programs that require individual proceedings.

The PAGA created a scheme to “deputize” private citizens – “aggrieved employees” – to sue their employers for violations of the California Labor Code on behalf of their co- workers as well as the State. If successful, aggrieved employees receive 25% of any recovered civil penalties and pass the other 75% to the California Labor and Workforce Development Agency (LWDA). The PAGA authorizes the attorneys who pursue the action to collect their attorney’s fees and costs in addition to the civil penalties. As a result, PAGA claims have exploded over the past two decades.

The Explosion Of PAGA Notices

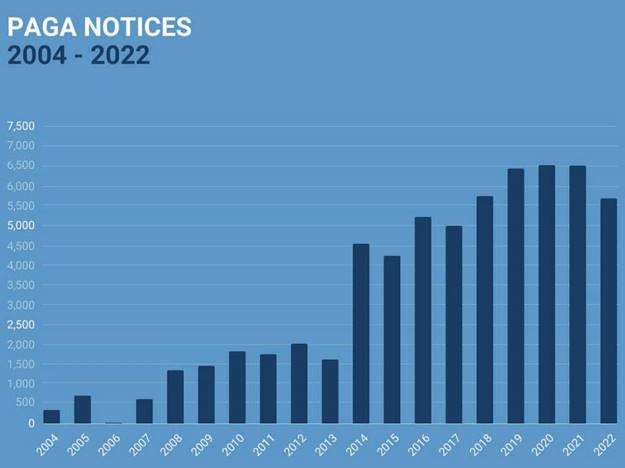

According to data maintained by the California Department of Industrial Relations, the number of PAGA notices filed with the LWDA has increased exponentially over the past two decades. The number grew from 11 notices in 2006 to 1,743 in 2011, to 5,208 in 2016, and to 6,502 in 2021. From 2013 to 2014, employers saw the largest single year increase, from 1,605 notices in 2013 to 4,532 notices in 2014, an increase of 182%. Over the five-year period from 2017 to 2021, the number of notices grew from 4,985 in 2017, to 6,502 in 2021, an increase of 30%.

The following chart illustrates this trend.

The increase is a likely reaction to the growth of workplace arbitration, fueled by the availability of fee-shifting.

The PAGA As A Work-Around To Arbitration

Although the proliferation of mandatory arbitration programs started as early as 1991 when the U.S. Supreme Court issued Gilmer, et al. v. Interstate/Johnson Lane Corp., 500 U.S. 20 (1991), the movement did not gain steam until 2011, when the U.S. Supreme Court issued its ruling in AT&T Mobility LLC v. Concepcion, et al., 563 U.S. 333 (2011), and held that the FAA preempts state rules that stand “as an obstacle to the accomplishment of the FAA’s objectives,” and it did not peak until 2018 with the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Epic Systems Corp. v. Lewis, et al., 138 S.Ct. 1612 (2018), wherein the last hurdle to enforcement of class and collective action waivers was eliminated.

As the adoption of arbitration programs gained popularity as a mechanism to contract around class and collective actions, the plaintiffs’ class action bar identified work-arounds. The California Supreme Court’s cemented the PAGA as the frontrunner for generated labor-related claims with its 2014 decision in Iskanian, et al. v. CLS Transportation Los Angeles, 59 Cal.4th 348 (Cal. 2014), which seemingly immunized the PAGA from arbitration programs. In Iskanian, the California Supreme Court held that “where an employment agreement compels the waiver of representative claims under the PAGA, it is contrary to public policy and unenforceable as a matter of state law.” Id. at 384. Whereas the California Supreme Court acknowledged Concepcion, it nevertheless reasoned that the rule against PAGA representative action waivers did not frustrate the FAA’s objectives because, whereas the FAA aims to ensure an efficient forum for the resolution of private disputes, a PAGA action “is a dispute between an employer and the state Labor and Workforce Development Agency.” Id.

The ruling likely fueled the filing of PAGA notices in 2014 and thereafter, as it cleared the PAGA as a mechanism by which to maintain a representative action unhindered by agreements to arbitrate on an individual basis. The PAGA workaround suffered its first significant set-back in 2022 with the U.S. Supreme Court’s highly anticipated decision in Viking River Cruises, Inc. v. Moriana, et al., 142 S.Ct. 1906 (2022), which addressed the arbitrability of PAGA claims.

The Dagger Of Viking River

In Viking River, the U.S. Supreme Court drove a dagger through the heart of this work- around by continuing its trend of enforcing the FAA over state efforts to avoid or flat-out prohibit arbitration. See, e.g., Cal. Lab. Code § 229 (“Actions to enforce the provisions of this article for the collection of due and unpaid wages claimed by an individual may be maintained without regard to the existence of any private agreement to arbitrate.”). The U.S. Supreme Court confirmed that, whether judicial or legislative in nature, where the FAA is in play, it preempts efforts to enforce those rules.

In Viking River, the U.S. Supreme Court found a conflict between the FAA and PAGA’s procedural structure. It recognized that the statute contains a “built-in mechanism of claim joinder,” which permits “aggrieved employees” to use the Labor Code violations they personally suffered as a basis to join to the action any claims that could have been raised by the State in an enforcement proceeding. Id. at 1923. It held that, to the extent that Iskanian precludes division of PAGA actions into individual and non-individual claims, and thereby “prohibits parties from contracting around this joinder device,” the FAA preempts such rule. Id.

Importantly, however, after finding that Viking should have been able to compel arbitration of plaintiff’s individual claim, the U.S. Supreme Court addressed “what the lower courts should have done with Moriana’s non-individual claims.” Id. at 1925. It ruled that, once an individual claim has been committed to a separate proceeding, the employee is no different from a member of the general public, and the PAGA provides no mechanism for such person to maintain suit. As a result, the correct course was to dismiss the remaining claims. Id.

As a result, the U.S. Supreme Court eviscerated perhaps the most popular work-around to workplace arbitration, dealing a significant blow to the plaintiffs’ bar and its ability to pursue claims on a representative basis.

What’s Next?

In her concurrence, Justice Sotomayor expressly opened the door to two potential solutions to the majority opinion. She suggested that, in its analysis of the parties’ contentions, the Supreme Court detailed “several important limitations on the pre-emptive effect of the [FAA],” meaning that “California is not powerless to address its sovereign concern that it cannot adequately enforce its Labor Code without assistance from private attorneys general.” Id. at 1925. First, she suggested that, if the majority was incorrect in its understanding that the plaintiff lacked “statutory standing” under the PAGA to litigate her “non-individual” claims separately, “California courts, in an appropriate case, will have the last word.” Second, alternatively, Justice Sotomayor opined that “the California Legislature is free to modify the scope of statutory standing under the PAGA within state and federal constitutional limits.” Id. at 1925-26.

Although the California State Legislature has not taken action, on July 20, 2022, the California Supreme Court granted review in Adolph, et al. v. Uber Technologies, Inc., No. G059860, on the question as to whether an aggrieved employee, who agreed to arbitrate claims under the PAGA that are “premised on Labor Code violations actually sustained by” the aggrieved employee, maintains standing to pursue “PAGA claims arising out of events involving other employees” in court or in any other forum agreed by the parties. The California Supreme Court is likely to issue a decision on these questions in 2023.

In the meantime, despite the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Viking River, many plaintiff’s attorneys have requested, and many California courts have granted, stays of representative claims, rather than dismissals, likely in order to preserve tolling in the event that the California Supreme Court fashions a rule that permits them to proceed with representative claims.