By Minh Duc Hoang and Quynh Nguyen

In recent years, many Chinese investors have silently participated in sensitive business sectors in Vietnam such as pawnbroking, real estate, content creating on digital platform, or business restricted to foreign capital. Such ‘silence’ stems from the fact that their names are not expressly indicated, but they often authorize Vietnamese individuals or enterprises to represent them—a mechanism commonly referred to as a nominee.

Although arising from the need to seek business opportunities in attractive yet restricted sectors, this mechanism harbors a risky legal ‘gray area’. So, what is the true nature of a nominee agreement? Is it legal in Vietnam? And what are the specific risks the parties might face?

The analysis below will provide a comprehensive overview, help you fully grasp the issue and serve as a basis for you to make the best decisions.

The analysis will be divided into three parts. Part 1 provides an analysis of the concepts of nominees, the practical use of the nominee in Vietnam, and Vietnamese legal regulations concerning nominees. Part 2 focuses on analyzing the legal consequences, risks, and the practice of Vietnamese courts in resolving disputes related to nominee agreements. Part 3 provides solutions to mitigate these risks.

Part 1

- How are Chinese investors currently engaging or asking Vietnamese people to act as nominees?

It is currently not difficult to find companies and projects owned by Vietnamese people on paper, but their capital sources and executive rights are actually under the hands of Chinese investors. They operate in many business sectors where Vietnamese law does not provide regulations on market access; has restrictions or prohibitions for foreign investors; or operate in sensitive areas for foreign investors, for example:

- Sensitive areas for security and national defense such as borders and islands.

- Digital content creation on media platforms (Tiktok, YouTube): Establishment of a ‘Vietnamese’ company for the purpose of leasing premises or employing creators.

- Purchase and receipt of the transfer of a house, land and other assets attached to land.

- Opening a pawnshop.

- Conditional business activities: Sectors reserved only for domestic investors or domestic investors holding controlling shares such as transportation, telecommunications, etc.

In practice, however, it appears that Chinese investors have been using Vietnamese nominees not only in restricted sectors but also in some sectors that are open to foreign investors. Particularly in manufacturing, Chinese investors would like to make use of two major advantages:

- Easy land acquisition. Authorize Vietnamese individuals or 100% domestically owned companies to facilitate the land acquisition for the production or construction of works in the energy sectors.

- Scrutiny reduction. 100% domestically owned companies are subject to less strict inspections by any regulatory authorities regarding environment, fire prevention, or other types of sub-licenses.

In reality, nominees’ activities represent a ‘gray area’ that is quite common and pose many legal risks for both foreign investors who have invested their capital and nominees themselves.

2. What is a nominee?

First, it’s necessary to understand what nominees and nominee agreements are.

Simply put, nominees are Vietnamese individuals, or, to a limited extent, legal entities, who are recorded in the legal documents (i.e., enterprise registration certificates, land use right certificates) as the owners, capital contribution members… however, they are not the persons who actually provide the funds, control and benefit from such investment.

The persons who actually provide their capital and management (the Chinese investors) are called the actual beneficial owners.

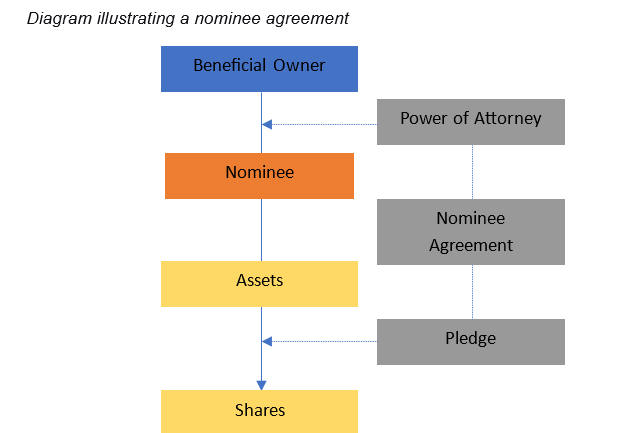

There are usually power of attorney agreements or implied agreements between both parties (which are not disclosed to any government authorities) with respect to any capital contribution, profit sharing, and executive rights. The beneficial owners, whose names are not recorded, still control the nominees through:

- Agreements and power of attorney: Execution of power of attorney agreements, custody agreements, undated share purchase and sale agreements or pre-signed land/house transfer agreements;

- Collateral: Pledge/holding of shares, certificates and seals; such agreements are also pre-signed but undated and can be registered with the Vietnamese registration authorities for secured transactions.

- Financial control: Control of bank accounts, profit transfer agreements.

- Liability binding: Penalty clauses, promissory notes.

- Actual management: Direct management of operations despite holding names.

3. What are the differences between nominee, trust and special ownership structure (VIE)?

To better understand the nature of the nominee, we will compare it with two other institutions and variations: Trust (Section 3) and special ownership structure – VIE (Section 4).

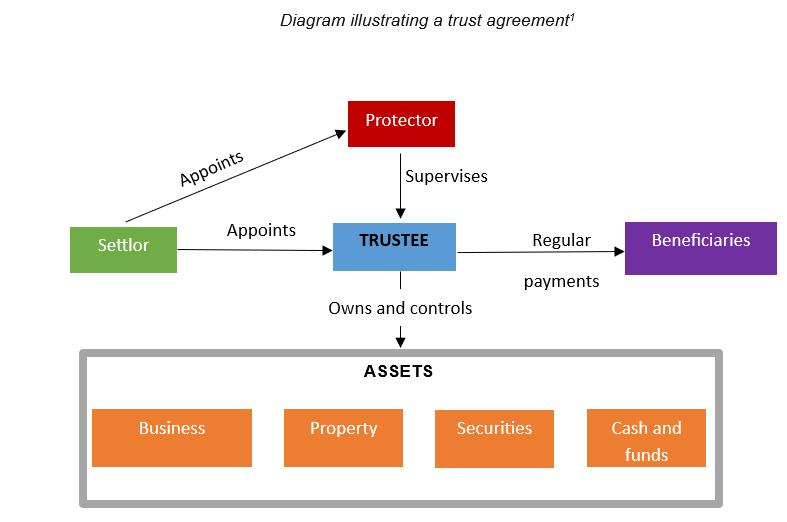

First of all, Trust. Simply put, it is a legal mechanism in which the settlor transfers its assets to the trustee to manage for the benefit of the beneficiary. In some cases, there is an additional protector to control or approve the trustee’s decisions.

Unlike many countries, Vietnamese law does not recognize the trust regime because it does not separate legal ownership and benefit rights. However, in practice, there are still some similar mechanisms, which apply to a limited extent, for example:

- Securities investment trust: Fund management companies are allowed to hold the titles and manage investment portfolios on behalf of clients. This form is similar to the ‘trust,’ however, it is only applicable in the securities sector.

- Investment fund: Fund management companies manage assets for investors, with some characteristics similar to the trust.

- Commodity trading trust: It is regulated in commercial law.

- Household assets: An individual can be authorized to represent an entire household in accordance with the Land Law.

In summary, Vietnam does not recognize trust in the international sense, but there are limited alternative mechanisms in some sectors.

4. If Chinese investors want to set up a VIE structure, whether such a structure is considered a nominee agreement?

VIE is a model commonly used in China. Accordingly, a foreign company (usually registered in the BVI or Cayman) sets up a 100% foreign-owned enterprise (WFOE) in China. The WFOE does not own shares directly, but signs many contracts (services, share pledges, options, etc.) to control and benefit economically from the Chinese companies.

This model helps Chinese companies in sectors that are limited to foreign capital (such as technology, education, media) to raise international capital and list abroad without violating ownership limits.

In comparison with the nominee, VIE is also intended to overcome any restrictions on investment, however, the differences are that the nominee only relies on one person, while VIE relies on a complex chain of contracts. China implicitly recognizes VIE, but basically does not accept nominee.

In Vietnam, some chains of pawnshops supported by Chinese investors have applied the VIE structure.

5. How does Vietnamese law regulate nominees?

Vietnamese law currently does not provide specific regulations on the nominee mechanism. However, if the nominees are understood as the persons who have been recorded as the owners, but not the actual beneficiaries, and concurrently there are only implied agreements between the parties, which are not disclosed with any third party (especially any government authorities), then it can be determined that such form is not recognized by Vietnamese law.

The reason is that under Vietnamese law, ownership rights—explicitly represented by the names recorded in documents, which recognize ownership rights such as the Red Book or the Shareholder Registration Book—are absolute. That means the owners have full rights to such assets, and execution of agreements to waive such rights does not automatically give the actual beneficiaries the relevant legal status.

Part 2

Following the previous analysis related to the concepts of nominees, the practice use of the nominees in Vietnam and Vietnamese legal regulations concerning nominees, Part 2 will focus on analyzing the legal consequences, risks as well as the trial practice of Vietnamese courts when disputes related to the nominee agreements arise and provide solutions to limit these risks.

6. What are the legal risks and the trial practice of Vietnamese courts?

When disputes arise between the Chinese beneficial owner and the nominee, Vietnamese courts tend to view the nominee transaction or its variants as sham transactions and therefore being invalid according to the 2015 Civil Code (Articles 117, 138): Civil transactions (power of attorney agreements, capital contribution agreements) established as shams (with the purpose of concealing another transaction) will be declared invalid.

If the nominee agreement involves implementing an investment project, including applying for an Investment Registration Certificate, Vietnamese Investment Law allows the licensing authority to terminate the project if a ‘sham/simulated transaction’ is discovered — which often applies to nominee structures used to circumvent sector restrictions.

In addition, parties may also be subject to administrative sanctions, for example, for contracts in illegal investment or business sectors.

In terms of trial practice, as mentioned above, after declaring the nominee transaction as a sham transaction invalid, the court will continue to consider the original transaction, that is, the hidden transaction, whether it is valid or not. If that transaction:

- Does not fall into the prohibited, restricted sectors or sectors requiring approvals for foreign investors or purchasers, the court will recognize the validity of this transaction and resolve the consequences of these transactions in the direction that ‘the parties will return everything they have received from each other’, or, in some cases, give the nominee a part of the benefits from the sale of the property or;

- Falls into the prohibited or restricted group, for example, real estate that foreign individuals are not allowed to buy, or industries not open or restrict to foreign investors where foreign investors are not allowed to buy shares or contribute capital, for example, e-commerce or pharmaceutical distribution; then it is highly likely that the court will declare the transaction invalid on the grounds of violating the prohibition prescribed by law. The investor can then only claim the money back, but cannot claim ownership of the related enterprise.

However, there was once a court judgment arguing that Vietnamese law does not prohibit nominee capital contribution, implying that nominee shares might be accepted in specific cases. However, as the judgment did not elaborate further, it is unclear if the court merely acknowledged an existing transaction status or implicitly affirmed that parties are allowed to perform any acts not prohibited by law.[3]

7. How do nominee disputes actually take place?

In practice, many disputes have occurred, especially in manufacturing, between Chinese beneficiary owners and Vietnamese nominees.

Notably, nominee agreements are often not designed with multiple layers (see Section 12 below) to prevent risks from the outset. Instead:

- Lack of preparation. There are often only very simple agreements on the nominee, cash transactions or phone contact, avoiding emails, leading to difficulty in proving.

- Lack of synchronization. Oral or sketchy written agreements make the implementation process different from the agreed-upon content, creating loopholes for disputes.

8. How do Chinese investors usually deal with disputes?

When a dispute arises, the parties often have three ways of handling:

- Criminal denunciation. Some parties seek to criminalize the dispute (report appropriation or abuse of trust), but are often unsuccessful due to a lack of evidence, and Vietnamese investigative agencies often tend to consider this a purely civil dispute.

- Withdrawal agreement. The Vietnamese and Chinese parties negotiate for the investor to get back part of the money, often with additional costs.

- Civil lawsuit. Bring the case to a competent court; the litigation process is lengthy, and the outcome depends on whether the original transaction violates the prohibition or not (as analyzed in the legal risks section in Section 6 of this article).

In most cases, the parties will follow the first option.

9. What is the impact on Chinese investors?

- Loss of assets. The person named on the documents has the legal right to dispose the assets (sell, donate, mortgage) without the actual owner’s consent. The fund provider can file a lawsuit to have the transaction declared invalid, but if the original agreement is not recognized by law, the maximum right is to claim the money already handed over. Even then, litigation and judgment enforcement often take many years.

- Exploitation. Furthermore, the nominee can exploit their legal position to give pressure for more money, or even ‘turn around’ and seize the company and all profits. In practice, many Chinese investors, especially small ones, get stuck in such nominal nominee agreements.

- Legal liability. The capital or assets do not fully shield them from legal liability. The actual owner may be administratively fined, or even criminally prosecuted, if the act is deemed a circumvention of law, illegal investment, or business. They might even be placed on a restricted entry list for Vietnam in the future.

- Inability to protect rights. When disputes occur, Chinese investors have almost no legal basis to protect themselves under Vietnamese law.

10. What are the impacts on the nominee?

When disputes occur, the nominee is not entirely off the hook and may face the following legal consequences:

- Legal liability. The nominee recorded on paper will bear full legal liability arising from the company, including debts, tax obligations, and even criminal liability if the company violates the law. The explosion at an aluminum smelting workshop in Dong Mai craft village, Van Lam, Hung Yen, which killed four and injured three, raised suspicions that the actual owner was Chinese but used a Vietnamese nominee.[4]

- Tax risks. Specifically, the tax authority may determine that profit transferred to the foreign investor constitutes taxable income for the nominee.

- Reputation risk. The nominee’s name is usually recorded on the Enterprise Registration Certificate. Changing the legal representative or transferring capital contributions usually requires approval from the Members’ Council or Board of Directors—where the representatives are often the Chinese investors who have left. When this procedure cannot be performed, the nominee is legally ‘stuck’, loses credibility, and may even be held jointly liable for the company’s activities, debts, or violations.

11. What are the new beneficiary owner regulations? And do they help prevent nominee agreements?

- What are the new beneficiary owner regulations and do they help prevent nominee agreements?

Effective July 1, 2025, the amended Enterprise Law and Decree 168/2025/ND-CP introduce new regulations on beneficiary owners (BO).

Enterprises, upon establishment or when changing registration content, must declare information about individuals owning directly or indirectly 25% of the charter capital or 25% of voting shares or more, or individuals having control over management, appointment, or dismissal of the legal representative, Board of Directors, Director/General Director.

Enterprises are obligated to maintain a list of BOs, update it upon changes, and submit this information to the Provincial Business Registration Agency. Competent state authorities have rights to access to this data in the National Database on Enterprise Registration for inspection, anti-money laundering, and enterprise management purposes.

If an enterprise fails to fulfill its declaration, update obligations, or declares false information, it may be administratively sanctioned according to current regulations on enterprise registration and the Enterprise Law.

Regarding nominee structures, the enterprise has no obligation to publicly disclose the nominee agreement, but if the individual truly behind the nominee meets the BO criteria, they must still be declared per the above procedure. Verifying actual control through layers of legal entities remains very difficult in practice, especially when BOs have cross-border investment activities.

Part 3

12. What should Chinese investors do then?

We always recommend that Chinese investors comply with Vietnamese regulations, specifically following these steps:

- Choose open sectors: First, foreign investors need to thoroughly research the list of investment sectors. Vietnam has many sectors that do not restrict foreign investors or allow ownership up to a certain ratio (e.g., 50%, 99%). In practice, many Chinese investors are ‘threatened’ by Vietnamese partners that they cannot invest as foreigners and must go through Vietnamese enterprises or individuals, even when these sectors are 100% open to foreign investors, such as wholesale or retail. Therefore, Chinese investors should first thoroughly understand their intended sector to proceed with transparent investment within the permitted framework.

- Choose related sectors: If the desired sector is restricted, consider an investment sector related to the initially intended one, or broad sectors like management consulting services, which are fully open to foreign investors.

- Use alternative structures: If still wishing to invest in restricted sectors, use complex but legal structures under the guidance of experienced lawyers, for example:

-Establishing different layers of companies so that the final subsidiary is considered a Vietnamese enterprise.

-Using Business Cooperation Contracts (BCC): signing with a Vietnamese partner as a form of joint venture, clearly dividing business products, revenue or profits.

-Investing through investment funds: Permitted Vietnamese funds can hold capital in sensitive enterprises, and foreign investors can invest in these funds.

-Using service provision contracts as in the VIE model mentioned above.

13. If using a nominee is unavoidable, what should be done?

This is a last-resort, high-risk solution. If compelled to use a nominee (e.g., not wishing to ‘show their face’ or entering sectors restricted by Vietnamese law), Chinese investors need protection through stringent measures, such as:

- Security measures: Require the nominee to mortgage their personal assets to you to ensure they do not ‘turn around’.

- Complete documentation and evidence. Have a detailed power of attorney agreement and clear payment receipts: Although still at risk of being declared invalid, it creates some moral and legal binding. Especially, it serves as evidence recording that the Chinese investor has given money to the nominee. Additionally, the investor can request the nominee to pre-sign specific undated contracts like share purchase/sale contracts, share pledge agreements, etc.

- Choose the right person: It should only be family members or extremely close partners.

- Accept the risk: Understand that the Chinese investors are betting their money on trust and could lose everything.

Conclusion: Vietnam’s trend towards information transparency and tighter management is very clear. The ‘gray area’ of nominees is increasingly shrinking. Professional, transparent investment not only ensures legal safety for Chinese investors but also builds a good image and enables sustainable development in this potential market.

Find a good lawyer before finding a nominee!

[1] Image source: https://garant.ae/en/insights/trusts-in-the-uae

[2] Diagram illustrating the special investment structure

[3] Appellate Commercial Business Judgment No. 36/2024/KDTM-PT dated 27 June 2024 of the High People’s Court in Ho Chi Minh City.

[4] However, this point has not yet been confirmed by mainstream media and needs to be verified.